Blender (software)

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The logo designed by Ton Roosendaal | |

Blender version 3.5.0 (2023) | |

| Original author(s) | Ton Roosendaal |

|---|---|

| Developer(s) | Blender Foundation, community |

| Initial release | January 2, 1994[1] |

| Stable release | 4.3[2] |

| Preview release | 4.4.0

/ October 2, 2024 |

| Repository | |

| Written in | C++, Python |

| Operating system | Linux, macOS, Windows, IRIX,[3] BSD,[4][5][6][7] Haiku[8] |

| Size | 294–934 MiB (varies by operating system)[9][10] |

| Available in | 36 languages |

List of languages Abkhaz, Arabic, Basque, Brazilian Portuguese, Castilian Spanish, Catalan, Croatian, Czech, Dutch, English (official), Esperanto, French, German, Hausa, Hebrew, Hindi, Hungarian, Indonesian, Italian, Japanese, Korean, Kyrgyz, Persian, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian, Serbian, Simplified Chinese, Slovak, Spanish, Swedish, Thai, Traditional Chinese, Turkish, Ukrainian, Vietnamese | |

| Type | 3D computer graphics software |

| License | GPL-2.0 or later[11] |

| Website | www |

Blender is a free and open-source 3D computer graphics software tool set that runs on Windows, MacOS, BSD, Haiku, IRIX and Linux. It is used for creating animated films, visual effects, art, 3D-printed models, motion graphics, interactive 3D applications, virtual reality, and, formerly, video games.

History

[edit]

Blender was initially developed as an in-house application by the Dutch animation studio NeoGeo (no relation to the video game brand), and was officially launched on January 2, 1994.[12] Version 1.00 was released in January 1995,[13] with the primary author being the company co-owner and software developer Ton Roosendaal. The name Blender was inspired by a song by the Swiss electronic band Yello, from the album Baby, which NeoGeo used in its showreel.[14][15][16] Some design choices and experiences for Blender were carried over from an earlier software application, called Traces, that Roosendaal developed for NeoGeo on the Commodore Amiga platform during the 1987–1991 period.[17]

On January 1, 1998, Blender was released publicly online as SGI freeware.[1] NeoGeo was later dissolved, and its client contracts were taken over by another company. After NeoGeo's dissolution, Ton Roosendaal founded Not a Number Technologies (NaN) in June 1998 to further develop Blender, initially distributing it as shareware until NaN went bankrupt in 2002. This also resulted in the discontinuation of Blender's development.[18]

In May 2002, Roosendaal started the non-profit Blender Foundation, with the first goal to find a way to continue developing and promoting Blender as a community-based open-source project. On July 18, 2002, Roosendaal started the "Free Blender" campaign, a crowdfunding precursor.[19][20] The campaign aimed at open-sourcing Blender for a one-time payment of €100,000 (USD 100,670 at the time), with the money being collected from the community.[21] On September 7, 2002, it was announced that they had collected enough funds and would release the Blender source code. Today, Blender is free and open-source software, largely developed by its community as well as 26 full-time employees and 12 freelancers employed by the Blender Institute.[22]

The Blender Foundation initially reserved the right to use dual licensing so that, in addition to GPL 2.0-or-later, Blender would have been available also under the "Blender License", which did not require disclosing source code but required payments to the Blender Foundation. However, this option was never exercised and was suspended indefinitely in 2005.[23] Blender is solely available under "GNU GPLv2 or any later" and was not updated to the GPLv3, as "no evident benefits" were seen.[24] The binary releases of Blender are under GNU GPLv3 or later because of the incorporated Apache libraries.[25]

In 2019, with the release of version 2.80, the integrated game engine for making and prototyping video games was removed; Blender's developers recommended that users migrate to more powerful open source game engines such as Godot instead.[26][27]

Suzanne

[edit]

In February 2002, the fate of the Blender software company, NaN, became evident as it faced imminent closure in March. Nevertheless, one more release was pushed out, Blender 2.25. As a sort of Easter egg and last personal tag, the artists and developers decided to add a 3D model of a chimpanzee head (called a "monkey" in the software). It was created by Willem-Paul van Overbruggen (SLiD3), who named it Suzanne, after the orangutan in the Kevin Smith film Jay and Silent Bob Strike Back.[28]

Suzanne is Blender's alternative to more common test models such as the Utah Teapot and the Stanford Bunny. A low-polygon model with only 500 faces, Suzanne is included in Blender and often used as a quick and easy way to test materials, animations, rigs, textures, and lighting setups. It is as easily added to a scene as primitives such as a cube or plane.[29]

The largest Blender contest gives out an award called the Suzanne Award,[30] underscoring the significance of this unique 3D model in the Blender community.

Features

[edit]Modeling

[edit]

Blender has support for a variety of geometric primitives, including polygon meshes, Bézier curves, NURBS surfaces, metaballs, icospheres, text, and an n-gon modeling system called B-mesh. There is also an advanced polygonal modelling system which can be accessed through an edit mode. It supports features such as extrusion, bevelling, and subdividing.[31]

Modifiers

[edit]Modifiers apply non-destructive effects which can be applied upon rendering or exporting, such as subdivision surfaces.

Sculpting

[edit]Blender has multi-resolution digital sculpting, which includes dynamic topology, "baking", remeshing, re-symmetrization, and decimation. The latter is used to simplify models for exporting purposes (an example being game assets).

Geometry nodes

[edit]

Blender has a node graph system for procedurally and non-destructively creating and manipulating geometry. It was first added to Blender 2.92, which focuses on object scattering and instancing.[32] It takes the form of a modifier, so it can be stacked over other different modifiers.[33] The system uses object attributes, which can be modified and overridden with string inputs. Attributes can include positions, normals and UV maps.[34] All attributes can be viewed in an attribute spreadsheet editor.[35] The Geometry Nodes utility also has the capability of creating primitive meshes.[36] In Blender 3.0, support for creating and modifying curves objects was added to Geometry Nodes;[37] in the same release, the Geometry Nodes workflow was completely redesigned with fields, in order to make the system more intuitive and work like shader nodes.[38][39]

Simulation

[edit]Blender can be used to simulate smoke, rain, dust, cloth, fluids, hair, and rigid bodies.[40]

Fluid simulation

[edit]

The fluid simulator can be used for simulating liquids, like water being poured into a cup.[41] It uses Lattice Boltzmann methods (LBM) to simulate fluids and allows for plenty of adjustment of particles and resolution. The particle physics fluid simulation creates particles that follow the smoothed-particle hydrodynamics method.[42]

Blender has simulation tools for soft-body dynamics, including mesh collision detection, LBM fluid dynamics, smoke simulation, Bullet rigid-body dynamics, an ocean generator with waves, a particle system that includes support for particle-based hair, and real-time control during physics simulation and rendering.

In Blender 2.82, a new fluid simulation system called Mantaflow was added, replacing the old FLIP system.[43] In Blender 2.92, another fluid simulation system called APIC, which builds on Mantaflow,[citation needed] was added. Vortices and more stable calculations are improved from the FLIP system.

Cloth Simulation

[edit]Cloth simulation is done by simulating vertices with a rigid body simulation. If done on a 3D mesh, it will produce similar effects as the soft body simulation.

Animation

[edit]Blender's keyframed animation capabilities include inverse kinematics, armatures, hooks, curve- and lattice-based deformations, shape keys, non-linear animation, constraints, and vertex weighting. In addition, its Grease Pencil tools allow for 2D animation within a full 3D pipeline.

Rendering

[edit]

Blender includes three render engines since version 2.80: EEVEE, Workbench and Cycles.

Cycles is a path tracing render engine. It supports rendering through both the CPU and the GPU. Cycles supports the Open Shading Language since Blender 2.65.[44]

Cycles Hybrid Rendering is possible in Version 2.92 with Optix. Tiles are calculated with GPU in combination with CPU.[45]

EEVEE is a new physically based real-time renderer. While it is capable of driving Blender's real-time viewport for creating assets thanks to its speed, it can also work as a renderer for final frames.

Workbench is a real-time render engine designed for fast rendering during modelling and animation preview. It is not intended for final rendering. Workbench supports assigning colors to objects for visual distinction.[46]

Cycles

[edit]Cycles is a path-tracing render engine that is designed to be interactive and easy to use, while still supporting many features.[47] It has been included with Blender since 2011, with the release of Blender 2.61. Cycles supports with AVX, AVX2 and AVX-512 extensions, as well as CPU acceleration in modern hardware.[48]

GPU rendering

[edit]Cycles supports GPU rendering, which is used to speed up rendering times. There are three GPU rendering modes: CUDA, which is the preferred method for older Nvidia graphics cards; OptiX, which utilizes the hardware ray-tracing capabilities of Nvidia's Turing architecture & Ampere architecture; HIP, which supports rendering on AMD Radeon graphics cards; and oneAPI for Intel Arc GPUs. The toolkit software associated with these rendering modes does not come within Blender and needs to be separately installed and configured as per their respective source instructions.

Multiple GPUs are also supported (with the notable exception of the EEVEE render engine[49]) which can be used to create a render farm to speed up rendering by processing frames or tiles in parallel—having multiple GPUs, however, does not increase the available memory since each GPU can only access its own memory.[50] Since Version 2.90, this limitation of SLI cards is broken with Nvidia's NVLink.[51]

Apple's Metal API got initial implementation in Blender 3.1 for Apple computers with M1 chips and AMD graphics cards.[52]

| Feature | CPU | CUDA | OPTIX [54] | HIP | oneAPI | Metal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hardware Minimum for 3.0 | x86-64 and other 64-Bit[55] | Cuda 3.0+: Nvidia cards Kepler to Ampere (CUDA Toolkit 11.1+)[56] | OptiX 7.3 with driver 470+: Full: Nvidia RTX Series; Parts: Maxwell+ | AMD RDNA architecture or newer, Radeon Software Drivers (Windows, Linux) | Intel Graphics Driver 30.0.101.3430 or newer on Windows, OpenCL runtime 22.10.23904 on Linux | Apple Computers with Apple Silicon in MacOS 12.2, AMD Graphics Cards with MacOS 12.3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Basic shading | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shadows | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Motion blur | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hair | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Volume | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Subsurface scattering | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Open Shading Language (1.11) (OSL 1.12.6 in 3.4) | Yes | No | Partial[57] | No | No | No | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Correlated multi-jittered sampling | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bevel and AO shaders | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Baking [58] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Can use CPU memory | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Distribute memory across devices | Yes render farm [59][60] | Yes with NVLink | Yes with NVLink | No | No | No | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Experimental features | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adaptive subdivision[61] | Experimental | Experimental | Experimental | Experimental | Experimental | Experimental | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Integrator

[edit]The integrator is the core rendering algorithm used for lighting computations. Cycles currently supports a path tracing integrator with direct light sampling. It works well for a variety of lighting setups, but it is not as suitable for caustics and certain other complex lighting situations. Rays are traced from the camera into the scene, bouncing around until they find a light source (a lamp, an object material emitting light, or the world background), or until they are simply terminated based on the number of maximum bounces determined in the light path settings for the renderer. To find lamps and surfaces emitting light, both indirect light sampling (letting the ray follow the surface bidirectional scattering distribution function, or BSDF) and direct light sampling (picking a light source and tracing a ray towards it) are used.[62]

The default path tracing integrator is a "pure" path tracer. This integrator works by sending several light rays that act as photons from the camera out into the scene. These rays will eventually hit either: a light source, an object, or the world background. If these rays hit an object, they will bounce based on the angle of impact, and continue bouncing until a light source has been reached or until a maximum number of bounces, as determined by the user, which will cause it to terminate and result in a black, unlit pixel. Multiple rays are calculated and averaged out for each pixel, a process known as "sampling". This sampling number is set by the user and greatly affects the final image. Lower sampling often results in more noise and has the potential to create "fireflies" (which are uncharacteristically bright pixels), while higher sampling greatly reduces noise, but also increases render times.

The alternative is a branched path tracing integrator, which works mostly the same way. Branched path tracing splits the light rays at each intersection with an object according to different surface components,[clarification needed] and takes all lights into account for shading instead of just one. This added complexity makes computing each ray slower but reduces noise in the render, especially in scenes dominated by direct (one-bounce) lighting. This was removed in Blender 3.0 with the advent of Cycles X, as improvements to the pure path tracing integrator made the branched path tracing integrator redundant [63]

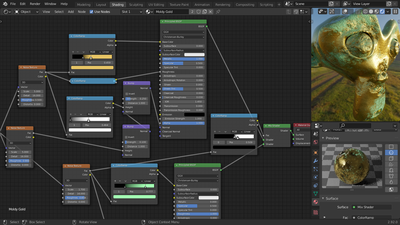

Open Shading Language

[edit]Blender users can create their own nodes using the Open Shading Language (OSL); this allows users to create stunning materials that are entirely procedural, which allows them to be used on any objects without stretching the texture as opposed to image-based textures which need to be made to fit a certain object. (Note that the shader nodes editor is shown in the image, although mostly correct, has undergone a slight change, changing how the UI is structured and looks. [64]

Materials

[edit]Materials define the look of meshes, NURBS curves, and other geometric objects. They consist of three shaders to define the mesh's surface appearance, volume inside, and surface displacement.[47]

The surface shader defines the light interaction at the surface of the mesh. One or more bidirectional scattering distribution functions, or BSDFs, can specify if incoming light is reflected, refracted into the mesh, or absorbed.[47] The alpha value is one measure of translucency.

When the surface shader does not reflect or absorb light, it enters the volume (light transmission). If no volume shader is specified, it will pass straight through (or be refracted, see refractive index or IOR) to another side of the mesh.

If one is defined, a volume shader describes the light interaction as it passes through the volume of the mesh. Light may be scattered, absorbed, or even emitted[clarification needed] at any point in the volume.[47]

The shape of the surface may be altered by displacement shaders. In this way, textures can be used to make the mesh surface more detailed.

Depending on the settings, the displacement may be virtual-only modifying the surface normals to give the impression of displacement (also known as bump mapping) – real, or a combination of real displacement with bump mapping.[47]

EEVEE

[edit]EEVEE (or Eevee) is a real-time PBR renderer included in Blender from version 2.8.[65] This render engine was given the nickname EEVEE,[66] after the Pokémon. The name was later made into the backronym "Extra Easy Virtual Environment Engine" or EEVEE.[67]

With the release of Blender 4.2 LTS[68] in July 2024, EEVEE received an overhaul by its lead developer, Clément Foucault, called EEVEE Next. EEVEE Next boasts a variety of new features for Blender's real-time and rasterised renderer, including screen-space global illumination (SSGI),[69] virtual shadowmapping, sunlight extraction from HDRIs, and a rewritten system for reflections and indirect lighting via light probe volumes and cubemaps.[70] EEVEE Next also brings improved volumetric rendering, along with support for displacement shaders and an improved depth of field system similar to Cycles.

Plans for future releases of EEVEE include support for hardware-accelerated ray-tracing[71] and continued improvements to performance and shader compilation.[71]

Workbench

[edit]Using the default 3D viewport drawing system for modeling, texturing, etc.[72]

External renderers

[edit]Free and open-source:[73]

- Mitsuba Renderer[74]

- YafaRay (previously Yafray)

- LuxCoreRender (previously LuxRender)

- Appleseed Renderer[75]

- POV-Ray

- NOX Renderer[76]

- Armory3D – a free and open source game engine for Blender written in Haxe[77]

- Radeon ProRender – Radeon ProRender for Blender

- Malt Render – a non-photorealistic renderer with GLSL shading capabilities[78]

- Pixar RenderMan – Blender render addon for RenderMan[79]

- Octane Render – OctaneRender plugin for Blender

- Indigo Renderer – Indigo for Blender

- V-Ray – V-Ray for Blender, V-Ray Standalone is needed for rendering

- Maxwell Render – B-Maxwell addon for Blender

- Thea Render – Thea for Blender[80]

- Corona Renderer – Blender To Corona exporter, Corona Standalone is needed for rendering[81]

Texturing and shading

[edit]Blender allows procedural and node-based textures, as well as texture painting, projective painting, vertex painting, weight painting and dynamic painting.

Post-production

[edit]

Blender has a node-based compositor within the rendering pipeline, which is accelerated with OpenCL, and in 4.0 it supports GPU. It also includes a non-linear video editor called the Video Sequence Editor (VSE), with support for effects like Gaussian blur, color grading, fade and wipe transitions, and other video transformations. However, there is no built-in multi-core support for rendering video with the VSE.

Plugins/addons and scripts

[edit]Blender supports Python scripting for the creation of custom tools, prototyping, importing/exporting from other formats, and task automation. This allows for integration with several external render engines through plugins/addons. Blender itself can also be compiled & imported as a python library for further automation and development.

File format

[edit]Blender features an internal file system that can pack multiple scenes into a single ".blend" file.

- Most of Blender's ".blend" files are forward, backward, and cross-platform compatible with other versions of Blender, with the following exceptions:

- Loading animations stored in post-2.5 files in Blender pre-2.5. This is due to the reworked animation subsystem introduced in Blender 2.5 being inherently incompatible with older versions.

- Loading meshes stored in post 2.63. This is due to the introduction of BMesh, a more versatile mesh format.

- Blender 2.8 ".blend" files are no longer fully backward compatible, causing errors when opened in previous versions.

- Many 3.x ".blend" files are not completely backwards-compatible as well, and may cause errors with previous versions.

- All scenes, objects, materials, textures, sounds, images, and post-production effects for an entire animation can be packaged and stored in a single ".blend" file. Data loaded from external sources, such as images and sounds, can also be stored externally and referenced through either an absolute or relative file path. Likewise, ".blend" files themselves can also be used as libraries of Blender assets.

- Interface configurations are retained in ".blend" files.

A wide variety of import/export scripts that extend Blender capabilities (accessing the object data via an internal API) make it possible to interoperate with other 3D tools.

Blender organizes data as various kinds of "data blocks" (akin to glTF), such as Objects, Meshes, Lamps, Scenes, Materials, Images, and so on. An object in Blender consists of multiple data blocks – for example, what the user would describe as a polygon mesh consists of at least an Object and a Mesh data block, and usually also a Material and many more, linked together. This allows various data blocks to refer to each other. There may be, for example, multiple Objects that refer to the same Mesh, and making subsequent editing of the shared mesh results in shape changes in all Objects using this Mesh. Objects, meshes, materials, textures, etc. can also be linked to other .blend files, which is what allows the use of .blend files as reusable resource libraries.

Import and export

[edit]The software supports a variety of 3D file formats for import and export, among them Alembic, 3D Studio (3DS), FBX, DXF, SVG, STL (for 3D printing), UDIM, USD, VRML, WebM, X3D and OBJ.[82]

Deprecated features

[edit]Blender Game Engine

[edit]The Blender Game Engine was a built-in real-time graphics and logic engine with features such as collision detection, a dynamics engine, and programmable logic. It also allowed the creation of stand-alone, real-time applications ranging from architectural visualization to video games. In April 2018, the engine was removed from the upcoming Blender 2.8 release series, due to updates and revisions to the engine lagging behind other game engines such as Unity and the open-source Godot.[26] In the 2.8 announcements, the Blender team specifically mentioned the Godot engine as a suitable replacement for migrating Blender Game Engine users.[27]

Blender Internal

[edit]Blender Internal, a biased rasterization engine and scanline renderer used in previous versions of Blender, was also removed for the 2.80 release in favor of the new "EEVEE" renderer, a realtime physically based renderer.[83]

User interface

[edit]

Commands

[edit]Most of the commands are accessible via hotkeys. There are also comprehensive graphical menus. Numeric buttons can be "dragged" to change their value directly without the need to aim at a particular widget, as well as being set using the keyboard. Both sliders and number buttons can be constrained to various step sizes with modifiers like the Ctrl and Shift keys. Python expressions can also be typed directly into number entry fields, allowing mathematical expressions to specify values.

Modes

[edit]Blender includes many modes for interacting with objects, the two primary ones being Object Mode and Edit Mode, which are toggled with the Tab key. Object mode is used to manipulate individual objects as a unit, while Edit mode is used to manipulate the actual object data. For example, an Object Mode can be used to move, scale, and rotate entire polygon meshes, and Edit Mode can be used to manipulate the individual vertices of a single mesh. There are also several other modes, such as Vertex Paint, Weight Paint, and Sculpt Mode.

Workspaces

[edit]The Blender GUI builds its tiled windowing system on top of one or multiple windows provided by the underlying platform. One platform window (often sized to fill the screen) is divided into sections and subsections that can be of any type of Blender's views or window types. The user can define multiple layouts of such Blender windows, called screens, and switch quickly between them by selecting from a menu or with keyboard shortcuts. Each window type's own GUI elements can be controlled with the same tools that manipulate the 3D view. For example, one can zoom in and out of GUI-buttons using similar controls, one zooms in and out in the 3D viewport. The GUI viewport and screen layout are fully user-customizable. It is possible to set up the interface for specific tasks such as video editing or UV mapping or texturing by hiding features not used for the task.

Development

[edit]

Since the opening of the source code, Blender has experienced significant refactoring of the initial codebase and major additions to its feature set.

Improvements include an animation system refresh;[84] a stack-based modifier system;[85] an updated particle system[86] (which can also be used to simulate hair and fur); fluid dynamics; soft-body dynamics; GLSL shaders support[87] in the game engine; advanced UV unwrapping;[88] a fully recoded render pipeline, allowing separate render passes and "render to texture"; node-based material editing and compositing; and projection painting.[89]

Part of these developments was fostered by Google's Summer of Code program, in which the Blender Foundation has participated since 2005.

Historically, Blender has used Phabricator to manage its development but due to the announcement in 2021 that Phabricator would be discontinued,[90] the Blender Institute began work on migrating to another software in early 2022.[91] After extensive debate on what software it should choose[92] it was finally decided to migrate to Gitea.[93] The migration from Phabricator to Gitea is currently a work in progress.[94]

Blender 2.8

[edit]Official planning for the next major revision of Blender after the 2.7 series began in the latter half of 2015, with potential targets including a more configurable UI (dubbed "Blender 101"), support for physically based rendering (PBR) (dubbed EEVEE for "Extra Easy Virtual Environment Engine") to bring improved realtime 3D graphics to the viewport, allowing the use of C++11 and C99 in the codebase, moving to a newer version of OpenGL and dropping support for versions before 3.2, and a possible overhaul of the particle and constraint systems.[95][96] Blender Internal renderer has been removed from 2.8.[83] Code Quest was a project started in April 2018 set in Amsterdam, at the Blender Institute.[97] The goal of the project was to get a large development team working in one place, in order to speed up the development of Blender 2.8.[97] By June 29, 2018, the Code Quest project ended, and on July 2, the alpha version was completed.[98] Beta testing commenced on November 29, 2018, and was anticipated to take until July 2019.[99] Blender 2.80 was released on July 30, 2019.[100]

Cycles X

[edit]On April 23, 2021, the Blender Foundation announced the Cycles X project, where they improved the Cycles architecture for future development. Key changes included a new kernel, removal of default tiled rendering (replaced by progressive refine), removal of branched path tracing, and the removal of OpenCL support. Volumetric rendering was also replaced with better algorithms.[101][102][103] Cycles X had only been accessible in an experimental branch[104] until September 21, 2021, when it was merged into the Blender 3.0 alpha.[105]

Support

[edit]Blender is extensively documented on its website.[106] There are also a number of online communities dedicated to support, such as the Blender Stack Exchange.[107]

Modified versions

[edit]Due to Blender's open-source nature, other programs have tried to take advantage of its success by repackaging and selling cosmetically modified versions of it. Examples include IllusionMage, 3DMofun, 3DMagix, and Fluid Designer,[108] the latter being recognized as Blender-based.

Use in industry

[edit]Blender started as an in-house tool for NeoGeo, a Dutch commercial animation company.[109] The first large professional project that used Blender was Spider-Man 2, where it was primarily used to create animatics and pre-visualizations for the storyboard department.[110]

The French-language film Friday or Another Day (Vendredi ou un autre jour [fr]) was the first 35 mm feature film to use Blender for all the special effects, made on Linux workstations.[111] It won a prize at the Locarno International Film Festival. The special effects were by Digital Graphics of Belgium.[112]

Tomm Moore's The Secret of Kells, which was partly produced in Blender by the Belgian studio Digital Graphics, has been nominated for an Oscar in the category "Best Animated Feature Film".[113] Blender has also been used for shows on the History Channel, alongside many other professional 3D graphics programs.[114]

Plumíferos, a commercial animated feature film created entirely in Blender,[115] had premiered in February 2010 in Argentina. Its main characters are anthropomorphic talking animals.

Special effects for episode 6 of Red Dwarf season X, screened in 2012, were created using Blender as confirmed by Ben Simonds of Gecko Animation.[116][117][118]

Blender was used for previsualization in Captain America: The Winter Soldier.[119]

Some promotional artwork for Super Smash Bros. for Nintendo 3DS and Wii U was partially created using Blender.[120]

The alternative hip-hop group Death Grips has used Blender to produce music videos. A screenshot from the program is briefly visible in the music video for Inanimate Sensation.[121]

The visual effects for the TV series The Man in the High Castle were done in Blender, with some of the particle simulations relegated to Houdini.[122][123][124]

NASA used Blender to develop an interactive web application Experience Curiosity to celebrate the 3rd anniversary of the Curiosity rover landing on Mars.[125] This app[126] makes it possible to operate the rover, control its cameras and the robotic arm and reproduces some of the prominent events of the Mars Science Laboratory mission.[127] The application was presented at the beginning of the WebGL section on SIGGRAPH 2015.[128][List entry too long] Blender is also used by NASA for many publicly available 3D models. Many 3D models on NASA's 3D resources page are in a native .blend format.[129]

Blender was used for both CGI and compositing for the movie Hardcore Henry.[130] The visual effects in the feature film Sabogal were done in Blender.[131] VFX supervisor Bill Westenhofer used Blender to create the character "Murloc" in the 2016 film Warcraft.[132]

Director David F. Sandberg used Blender for multiple shots in Lights Out,[133] and Annabelle: Creation.[134][135]

Blender was used for parts of the credit sequences in Wonder Woman[136]

Blender was used for doing the animation in the film Cinderella the Cat.[137]

VFX Artist Ian Hubert used Blender for the science fiction film Prospect.[138] The 2018 film Next Gen was fully created in Blender by Tangent Animation. A team of developers worked on improving Blender for internal use, but it is planned to eventually add those improvements to the official Blender build.[139][140]

The 2019 film I Lost My Body was largely animated using Blender's Grease Pencil tool by drawing over CGI animation allowing for a real sense of camera movement that is harder to achieve in purely traditionally drawn animation.[141]

Ubisoft Animation Studio will use Blender to replace its internal content creation software starting in 2020.[142]

Khara and its child company Project Studio Q are trying to replace their main tool, 3ds Max, with Blender. They started "field verification" of Blender during their ongoing production of Evangelion: 3.0+1.0.[143] They also signed up as Corporate Silver and Bronze members of Development Fund.[144][145][146]

The 2020 film Wolfwalkers was partially created using Blender.[147]

The 2021 Netflix production Maya and the Three was created using Blender.[148]

In 2021 SPA Studios started hiring Blender artists[149] and as of 2022, contributes to Blender Development.[150] Warner Bros. Animation started hiring Blender artists in 2022.[151]

VFX company Makuta VFX used Blender for the VFX for Indian blockbuster RRR.[152]

Blender was used in several cases for the 2023 film Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse. Sony Pictures Imageworks, the primary studio behind the film's animation, used Blender's Grease Pencil for adding line-work and 2D FX animation alongside 3D models.[153] [154] At 14 years old, Canadian animator Preston Mutanga used Blender to create the Lego-style sequence in the film.[155] Mutanga was recruited after his fan-made Lego-style recreation of the film's teaser caught the attention of the filmmakers.[156]

The 2024 Lativan film Flow was made entirely in Blender and was rendered in EEVEE[157][158].

Open projects

[edit]Since 2005, every one to two years the Blender Foundation has announced a new creative project to help drive innovation in Blender.[159][160] In response to the success of the first open movie project, Elephants Dream, in 2006, the Blender Foundation founded the Blender Institute to be in charge of additional projects, such as films: Big Buck Bunny, Sintel, Tears of Steel; and Yo Frankie!, or Project Apricot, an open game utilizing the Crystal Space game engine that reused some of the assets created for Big Buck Bunny.

Online services

[edit]Blender Foundation

[edit]Blender Studio

[edit]The Blender Studio platform, launched in March 2014 as Blender Cloud,[161][162][163] is a subscription-based cloud computing platform where members can access Blender add-ons, courses and to keep track of the production of Blender Studio's open movies.[164] It is currently operated by the Blender Studio, formerly a part of the Blender Institute.[22] It was launched to promote and fundraiser for Project: Gooseberry, and is intended to replace the selling of DVDs by the Blender Foundation with a subscription-based model for file hosting, asset sharing and collaboration.[161][165] Blender Add-ons included in Blender Studio are CloudRig,[166] Blender Kitsu,[167] Contact sheet Add-on,[168] Blender Purge[169] and Shot Builder.[170][171][172] It was rebranded from Blender Cloud to Blender Studio on 22 October 2021.[173]

The Blender Development Fund

[edit]The Blender Development Fund is a subscription where individuals and companies can fund Blender's development.[174] Corporate members include Epic Games,[175] Nvidia,[176] Microsoft,[177] Apple,[178] Unity,[179] Intel,[180] Decentraland,[181] Amazon Web Services,[182] Meta,[183] AMD,[184] Adobe[185] and many more. Individual users can also provide one-time donations to Blender via payment card, PayPal, wire transfer, and some cryptocurrencies.[186]

Blender ID

[edit]The Blender ID is a unified login for Blender software and service users, providing a login for Blender Studio, the Blender Store, the Blender Conference, Blender Network, Blender Development Fund, and the Blender Foundation Certified Trainer Program.[187]

Blender Open Data

[edit]

The Blender Open Data is a platform to collect, display, and query benchmark data produced by the Blender community with related Blender Benchmark software.[188]

Blender Network

[edit]The Blender Network was an online platform to enable online professionals to conduct business with Blender and provide online support.[189] It was terminated on 31 March 2021.[190]

Blender Store

[edit]A store to buy Blender merchandise, such as shirts, socks, beanies, etc.[191]

Blender Extensions

[edit]Blender Extensions acts as the main repo for extensions, introduced in Blender 4.2, which include both addons and themes. Users can then install and update extensions right in Blender itself.[192]

Release history

[edit]This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: Overly detailed changelog relying entirely on primary sources. (August 2023) |

The following table lists notable developments during Blender's release history: green indicates the current version, yellow indicates currently supported versions, and red indicates versions that are no longer supported (though many later versions can still be used on modern systems).[citation needed]

| Version | Release date[193] | Notes and key changes |

|---|---|---|

| 1.00 | January 1994 | Blender in development.[194] |

| 1.23 | January 1998 | SGI version released, IrisGL.[194] |

| 1.30 | April 1998 | Linux and FreeBSD version, port to OpenGL and X11.[194] |

| 1.4x | September 1998 | Sun and Linux Alpha version released.[194] |

| 1.50 | November 1998 | First Manual published.[194] |

| 1.60 | April 1999 | New features behind a $95 lock. Windows version released.[194] |

| 1.6x | June 1999 | BeOS and PPC version released.[194] |

| 1.80 | June 2000 | Blender freeware again.[194] |

| 2.00 | August 2000 | Interactive 3D and real-time engine.[194] |

| 2.03 | 2000 | Handbook The official Blender 2.0 guide. |

| 2.10 | December 2000 | New engine, physics, and Python.[194] |

| 2.20 | August 2001 | Character animation system.[194] |

| 2.21 | October 2001 | Blender Publisher launch.[194] |

| 2.2x | December 2001 | Apple macOS version.[194] |

| 2.25 | October 13, 2002 | Blender Publisher freely available.[194] |

| 2.26 | February 2003 | The first truly open source Blender release.[194] |

| 2.30 | November 22, 2003 | New GUI; edits are now reversible. |

| 2.32 | February 3, 2004 | Ray tracing in internal renderer; support for YafaRay. |

| 2.34 | August 5, 2004 | LSCM-UV-Unwrapping, object-particle interaction. |

| 2.37 | May 31, 2005 | Simulation of elastic surfaces; improved subdivision surface. |

| 2.40 | December 22, 2005 | Greatly improved system and character animations (with a non-linear editing tool), and added a fluid and hair simulator. New functionality was based on Google Summer of Code 2005.[195] |

| 2.41 | January 25, 2006 | Improvements of the game engine (programmable vertex and pixel shaders, using Blender materials, split-screen mode, improvements to the physics engine), improved UV mapping, recording of the Python scripts for sculpture or sculpture works with the help of grid or mesh (mesh sculpting) and set-chaining models. |

| 2.42 | July 14, 2006 | The film Elephants Dream resulted in high development as a necessity. In particular, the Node-System (Material- and Compositor) has been implemented. |

| 2.43 | February 16, 2007 | Sculpt-Modeling as a result of Google Summer of Code 2006. |

| 2.46 | May 19, 2008 | With the production of Big Buck Bunny, Blender gained the ability to produce grass quickly and efficiently.[196] |

| 2.48 | October 14, 2008 | Due to development of Yo Frankie!, the game engine was improved substantially.[197] |

| 2.49 | June 13, 2009 | New window and file manager, new interface, new Python API, and new animation system.[198] |

| 2.57 | April 13, 2011 | First official stable release of 2.5 branch: new interface, new window manager and rewritten event — and tool — file processing system, new animation system (each setting can be animated now), and new Python API.[199] |

| 2.58 | June 22, 2011 | New features, such as the addition of the warp modifier and render baking. Improvements in sculpting.[200] |

| 2.58a | July 4, 2011 | Some bug fixes, along with small extensions in GUI and Python interface.[201] |

| 2.59 | August 13, 2011 | 3D mouse support. |

| 2.60 | October 19, 2011 | Developer branches integrated into the main developer branch: among other things, B-mesh, a new rendering/shading system, NURBS, to name a few, directly from Google Summer of Code. |

| 2.61 | December 14, 2011 | New Render Engine, Cycles, added alongside Blender Internal (as a "preview release").[202] Motion Tracking, Dynamic Paint, and Ocean Simulator. |

| 2.62 | February 16, 2012 | Motion tracking improvement, further expansion of UV tools, and remesh modifier. Cycles render engine updates to make it more production-ready. |

| 2.63 | April 27, 2012 | Bug fixes, B-mesh project: completely new mesh system with n-corners, plus new tools: dissolve, inset, bridge, vertex slide, vertex connect, and bevel. |

| 2.64 | October 3, 2012 | Green screen keying, node-based compositing. |

| 2.65 | December 10, 2012 | Over 200 bug fixes, support for the Open Shading Language, and fire simulation. |

| 2.66 | February 21, 2013[203] | Rigid body simulation available outside of the game engine, dynamic topology sculpting, hair rendering now supported in Cycles. |

| 2.67 | May 7–30, 2013[204] | Freestyle rendering mode for non-photographic rendering, subsurface scattering support added the motion tracking solver is made more accurate and faster, and an add-on for 3D printing now comes bundled. |

| 2.68 | July 18, 2013[205] | Rendering performance is improved for CPUs and GPUs, support for Nvidia Tesla K20, GTX Titan and GTX 780 GPUs. Smoke rendering improved to reduce blockiness. |

| 2.69 | October 31, 2013[206] | Motion tracking now supports plane tracking, and hair rendering has been improved. |

| 2.70 | March 19, 2014[207] | Initial support for volume rendering and small improvements to the user interface. |

| 2.71 | June 26, 2014[208] | Support for baking in Cycles and volume rendering branched path tracing now renders faster. |

| 2.72 | October 4, 2014[209] | Volume rendering for GPUs, more features for sculpting and painting. |

| 2.73 | January 8, 2015[210] | New fullscreen mode, improved Pie Menus, 3D View can now display the world background. |

| 2.74 | March 31, 2015[211] | Cycles got several precision, noise, speed, memory improvements, and a new Pointiness attribute. |

| 2.75a | July 1, 2015[212] | Blender now supports a fully integrated Multi-View and Stereo 3D pipeline, Cycles has much-awaited initial support for AMD GPUs, and a new Light Portals feature. |

| 2.76b | November 3, 2015[213] | Cycles volume density render, Pixar OpenSubdiv mesh subdivision library, node inserting, and video editing tools. |

| 2.77a | April 6, 2016[214] | Improvements to Cycles, new features for the Grease Pencil, more support for OpenVDB, updated Python library and support for Windows XP has been removed. |

| 2.78c | February 28, 2017[215] | Spherical stereo rendering for virtual reality, Grease Pencil improvements for 2D animations, Freehand curves drawing over surfaces, Bendy Bones, Micropolygon displacements, and Adaptive Subdivision. Cycles performance improvements. |

| 2.79b | September 11, 2017[216] | Cycles denoiser, improved OpenCL rendering support, Shadow Catcher, Principled BSDF Shader, Filmic color management, improved UI and Grease Pencil functionality, improvements in Alembic import and export, surface deformities modifier, better animation keyframing, simplified video encoding, Python additions and new add-ons. |

| 2.80 | July 30, 2019[217] | Revamped UI, added a dark theme, EEVEE realtime rendering engine on OpenGL, Principled shader, Workbench viewport, Grease Pencil 2D animation tool, multi-object editing, collections, GPU+CPU rendering, Rigify. |

| 2.81a | November 21, 2019[218] | OpenVDB voxel remesh, QuadriFlow remesh, transparent BSDF, brush curves preset in sculpting, WebM support. |

| 2.82 | February 14, 2020[219] | Improved fluid and smoke simulation (using Mantaflow), UDIM support, USD export and 2 new sculpting tools. |

| 2.83 LTS |

June 3, 2020[220] | Introduction of the Long Term Support (LTS) program, VDB files support, VR scene inspection, new cloth sculpt brush and viewport denoising. |

| 2.90 | August 31, 2020[221] | Physically based Nishita Sky Texture, improved EEVEE motion blur, sculpting improvements including a new multiresolution modifier and modelling improvements. |

| 2.91 | November 25, 2020[222] | Cloth Brush improvements, new sculpting Trim tool, new mesh boolean solver, volume to mesh and mesh to volume modifiers and customisable curve bevels. |

| 2.92 | February 25, 2021[223] | New Geometry Nodes procedural modelling system, New interactive Add Primitive Tool, sculpting improvements and Grease Pencil improvements. |

| 2.93 LTS |

June 2, 2021[224] | Expansion of Geometry Nodes with mesh primitives and a new spreadsheet editor, sculpting improvements, new grease pencil line art modifier and EEVEE rendering improvements. |

| 3.0 | December 3, 2021[225] | Major Cycles update with rewritten GPU kernels and rewritten shadow catchers and other rendering improvements. Overhaul to Geometry nodes with new 'Fields' system. A new UI visual refresh as well as other features and improvements. |

| 3.1 | March 9, 2022[226] | Point cloud objects, Cycles Metal Backend and new geometry nodes. |

| 3.2 | June 8, 2022[227] | Cycles light groups, shadow caustics rendering, sculpt mode painting and collection support in the asset browser. |

| 3.3 LTS |

September 7, 2022[228] | New procedural hair system with geometry nodes, support for Intel Arc GPUs and new geometry nodes. |

| 3.4 | December 7, 2022[229] | Path Guiding in Cycles, auto masking in sculpt mode, new UV relax tool and new geometry nodes. |

| 3.5 | March 29, 2023[230] | New hair system with Geometry nodes and asset browser, real-time viewport compositor, vector displacement maps for sculpting, viewport performance improvements with Apple Metal. |

| 3.6 LTS |

June 27, 2023 [231] | Simulation Nodes, rendering performance improvements on AMD Hardware and better UV packing. |

| 4.0 | November 14, 2023[232] | Cycles light linking, improved Principled BSDF shader, better Color management with the AgX tone mapper, and Geometry Nodes improvements. |

| 4.1 | March 26, 2024[233] | Geometry nodes baking, OpenImageDenoise performance improvements and viewport compositor improvements. |

| 4.2 LTS |

July 16, 2024[234] | Rewrite of the EEVEE render engine to be closer to cycles, addition of Ray Portal BSDF in Cycles, addition of Khronos PBR Neutral tone mapping, and GPU acceleration for the compositor.[235] |

| 4.3 | November 19, 2024[236] | Multi-pass compositing support for EEVEE, hardware accelerated ray tracing support for Linux, geometry node support for grease pencil.[237] |

| 4.4 Alpha |

Full release planned for approximately March 18, 2025. [238] | "Slotted" actions.[239] |

| 4.5 | Start of development planned for approximately February 5, 2025.[240] | There are no changes as of February 15, 2024. |

Legend: Old version, not maintained Old version, still maintained Latest version Latest preview version Future release | ||

As of 2021, official releases of Blender for Microsoft Windows, macOS and Linux,[241] as well as a port for FreeBSD,[242] are available in 64-bit versions. Blender is available for Windows 8.1 and above, and Mac OS X 10.13 and above.[243][244]

Blender 2.76b was the last supported release for Windows XP and version 2.63 was the last supported release for PowerPC. Blender 2.83 LTS and 2.92 were the last supported versions for Windows 7.[245] In 2013, Blender was released on Android as a demo, but has not been updated since.[246]

See also

[edit]- CAD library

- MB-Lab, a Blender add-on for the parametric 3D modeling of photorealistic humanoid characters

- MakeHuman

- List of free and open-source software packages

- List of video editing software

- List of 3D printing software

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Blender's 25th birthday!". blender.org. January 2, 2019. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- ^ "A Stroke of Genius". 19 November 2024. Retrieved 19 November 2024.

- ^ "Index of /release/Blender1.0//". download.blender.org. Retrieved 2024-11-04.

- ^ "FreshPorts -- graphics/blender: 3D modeling/rendering/animation/gaming package". www.freshports.org.

- ^ "OpenPorts.se | The OpenBSD package collection". openports.se. Archived from the original on 2020-07-26. Retrieved 2019-06-19.

- ^ "pkgsrc.se | The NetBSD package collection". pkgsrc.se.

- ^ "The dedicated application build system for DragonFly BSD: DragonFlyBSD/DPorts". July 23, 2019 – via GitHub.

- ^ "GitHub - haikuports/haikuports: Software ports for the Haiku operating system". July 27, 2019 – via GitHub.

- ^ "Blender 4.1 Release Index". blender.org. Retrieved June 6, 2024.

- ^ "Download — blender.org". blender.org. Retrieved June 6, 2024.

- ^ "License - blender.org". Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- ^ "How Blender started, twenty years ago…". Blender Developers Blog. Blender Foundation. Retrieved 2019-01-10.

- ^ "Doc:DK/2.6/Manual - BlenderWiki". Blender.org. Retrieved 2019-01-11.

- ^ "Ton Roosendaal Reveals the Origin of Blender's name". BlenderNation. 2021-10-19. Retrieved 2021-10-20.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "NeoGeo — Blender". YouTube. 2011-10-28. Retrieved 2019-06-11.

- ^ Kassenaar, Joeri (2006-07-20). "Brief history of the Blender logo—Traces". Archived from the original on 2010-01-22. Retrieved 2010-01-22.

- ^ "Blender's prehistory - Traces on Commodore Amiga (1987-1991)". zgodzinski.com.

- ^ "Blender History". Blender.org. Retrieved March 29, 2018.

- ^ "Blender Foundation Launches Campaign to Open Blender Source". Linux Today. Archived from the original on 2020-11-28. Retrieved 2017-01-22.

- ^ "Free Blender campaign". 2002-10-10. Archived from the original on 2002-10-10. Retrieved 2017-01-22.

- ^ "members". 2002-10-10. Archived from the original on 2002-10-10. Retrieved 2017-01-22.

- ^ a b "Blender.org About". Amsterdam. Retrieved 2021-02-01.

- ^ Roosendaal, Ton (June 2005). "Blender License". Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved January 19, 2007.

- ^ Prokoudine, Alexandre (26 January 2012). "What's up with DWG adoption in free software?". libregraphicsworld.org. Archived from the original on 9 November 2016. Retrieved 2015-12-05.

[Blender's Ton Roosendaal:] Blender is also still 'GPLv2 or later'. For the time being we stick to that, moving to GPL 3 has no evident benefits I know of. My advice for LibreDWG: if you make a library, choosing a widely compatible license (MIT, BSD, or LGPL) is a very positive choice.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "License". blender.org. Retrieved 2024-06-17.

- ^ a b "rB159806140fd3". developer.blender.org. Retrieved 2019-02-28.

- ^ a b "Blender 2.80 release". blender.org. Retrieved 2020-01-16.

- ^ "Meet Suzanne, the Blender Monkey". dummies. Retrieved 2024-01-22.

- ^ "Primitives — Blender Manual". docs.blender.org. Retrieved 2023-08-26.

- ^ Blender Foundation (2019). "Suzanne Awards 2019". Conference.blender.org. Retrieved 2022-07-19.

- ^ "Editing — Blender Manual". docs.blender.org. Retrieved 2022-03-18.

- ^ "Blender 2.92 Release Notes". blender.org. Archived from the original on 2021-02-25.

- ^ "Geometry Nodes Modifier — Blender Manual". docs.blender.org. Retrieved 2021-10-08.

- ^ "Attributes — Blender Manual". docs.blender.org. Retrieved 2021-10-08.

- ^ "Spreadsheet — Blender Manual". docs.blender.org. Retrieved 2021-10-08.

- ^ "Mesh Primitive Nodes — Blender Manual". docs.blender.org. Retrieved 2021-10-08.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "Procedural Curves in 3.0 and Beyond". Blender Developers Blog. Retrieved 2021-09-27.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "Attributes and Fields". Blender Developers Blog. Retrieved 2021-10-02.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Geometry Nodes Fields: Explained!, 30 September 2021, retrieved 2021-10-02

- ^ "Introduction to Physics Simulation — Blender Reference Manual". www.blender.org. Retrieved 2015-12-02.

- ^ "Create a Realistic Water Simulation – Blender Guru". Blender Guru. 9 November 2011. Retrieved 2015-12-02.

- ^ "Fluid Physics — Blender Reference Manual". www.blender.org. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2015-12-02.

- ^ "Reference/Release Notes/2.82 - Blender Developer Wiki". wiki.blender.org. Retrieved 2020-06-10.

- ^ "Cycles support OpenSL shading". blender.org. Archived from the original on January 25, 2013. Retrieved January 26, 2013.

- ^ "RBbfb6fce6594e".

- ^ Blender Documentation Team. "Rendering - Workbench - Introduction". Blender Manual. Retrieved 2023-02-07.

- ^ a b c d e "Introduction — Blender Reference Manual". www.blender.org. Retrieved 2015-10-18.

- ^ Jaroš, Milan; Strakoš, Petr; Říha, Lubomír. "Rending in Blender Cycles Using AVX-512 Vectorization" (PDF). Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- ^ "Limitations — Blender Manual". www.blender.org. Retrieved 2023-01-12.

- ^ "GPU Rendering — Blender Reference Manual". www.blender.org. Retrieved 2015-10-18.

- ^ "Blender 2.90: Cycles updates in Multi GPU (NVLink) • Blender 3D Architect". 10 August 2020.

- ^ "Reference/Release Notes/3.1/Cycles - Blender Developer Wiki".

- ^ "GPU Rendering — Blender Manual".

- ^ "Cycles Optix feature completeness". Blender Projects.

- ^ "Debian -- Package Search Results -- blender". packages.debian.org.

- ^ "Building Blender/CUDA - Blender Developer Wiki".

- ^ "Open Shading Language - Blender 4.1 Manual".

- ^ "Render Baking — Blender Manual".

- ^ "rentaflop".

- ^ "SheepIt Render Farm".

- ^ "Adaptive Subdivision — Blender Manual".

- ^ "Integrator — Blender Reference Manual". www.blender.org. Archived from the original on 2015-10-09. Retrieved 2015-10-18.

- ^ "Cycles X". Blender Developer Blog. Archived from the original on 2024-07-06. Retrieved 2024-07-16.

- ^ "Shader Nodes — Blender Manual".

- ^ "Eevee Roadmap". Code.blender.org. 2017-03-23. Retrieved 2019-06-11.

- ^ Roosendaal, Ton. "Ton Roosendaal - EEVEE". Twitter. Retrieved 2019-06-11.

- ^ "Blender Developers Blog - Viewport Project – Plan of Action". Code.blender.org. 2016-12-15. Retrieved 2019-06-11.

- ^ "4.2 LTS - Blender Developer Documentation". developer.blender.org. Retrieved 2024-07-26.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "EEVEE's Future". Blender Developers Blog. Retrieved 2024-07-26.

- ^ blender. "EEVEE-Next". Blender Projects. Retrieved 2024-07-26.

- ^ a b Foundation, Blender. "EEVEE Next Generation in Blender 4.2 LTS". Blender Developers Blog. Retrieved 2024-07-26.

- ^ "Ton Roosendaal on Twitter". Twitter. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

- ^ "External Renderers". Archived from the original on 2018-03-09. Retrieved 2018-06-14.

- ^ "Mitsuba Renderer". BlenderNation. 24 November 2010.

- ^ "Appleseed Renderer". BlenderNation. 2 May 2012.

- ^ "Getting started with NOX Renderer in Blender". BlenderNation. 3 September 2014.

- ^ "Armory - 3D Engine". armory3d.org. Retrieved 2022-01-05.

- ^ "malt-render". malt3d.com. Retrieved 2022-01-01.

- ^ "RenderMan for Blender 24.0". Renderman Documentation. Retrieved 2022-01-05.

- ^ "Blender Add-on for Thea Render". BlenderNation. 3 October 2013.

- ^ "Blender & Corona Renderer Tutorial". BlenderNation. 13 November 2014.

- ^ "Importing & Exporting Files — Blender Manual". docs.blender.org.

- ^ a b "Blender Internal renderer removed from 2.8". BlenderNation. April 19, 2018.

- ^ "Blender Animation system refresh project". blender.org. Retrieved 2019-01-14.

- ^ "Modifiers". blender.org. Retrieved 2019-01-14.

- ^ "New Particle options and Guides". Blender.org. Retrieved 2012-07-06.

- ^ "GLSL Pixel and Vertex shaders". Blender.org. Retrieved 2012-07-06.

- ^ "Subsurf UV Mapping". Blender.org. Retrieved 2012-07-06.

- ^ "Dev:Ref/Release Notes/2.49/Projection Paint – BlenderWiki". blender.org. June 3, 2009. Retrieved 2019-01-14.

- ^ "✩ Phacility is Winding Down Operations". admin.phacility.com. Retrieved 2022-08-09.

- ^ GitLab? Gitea? Call for participation on the future of Blender's development platform, 16 March 2022, retrieved 2022-08-09

- ^ "Developer.blender.org - Call for comments and participation". Blender Developer Talk. 2022-03-16. Retrieved 2022-08-09.

- ^ Marijnissen, Arnd (2022-06-27). "[Bf-committers] Gitea as choice for Phabricator migration. Reasons and timeline". Retrieved 2022-08-09.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "Gitea Diaries: Part 1". Blender Developers Blog. Retrieved 2022-08-09.

- ^ "Blender 2.8 – the Workflow release". code.blender.org. June 20, 2015. Retrieved September 9, 2017.

- ^ "2.8 project developer kickoff meeting notes". code.blender.org. November 1, 2015. Retrieved September 9, 2017.

- ^ a b Foundation, Blender. "Announcing Blender 2.8 Code Quest — blender.org". blender.org. Retrieved 2018-07-07.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "Beyond the Code Quest — Blender Developers Blog". Blender Developers Blog. Retrieved 2018-07-07.

- ^ "2.80 Release Plan --- Blender Developers Blog". blender.org. April 12, 2019. Retrieved April 18, 2019.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "Release Notes". blender.org. Retrieved 2019-08-14.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "Cycles X". Blender Developers Blog. Retrieved 2021-05-01.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Cycles X, 23 April 2021, retrieved 2021-05-01

- ^ "Blender Announces Cycles X: The Blazingly Fast Future of Cycles". BlenderNation. 2021-04-23. Retrieved 2021-05-01.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "Blender Experimental Builds - blender.org". Blender Experimental Builds - blender.org. Retrieved 2021-05-01.

- ^ "Cycles X now in Blender 3.0 alpha!". BlenderNation. 2021-09-21. Retrieved 2021-09-23.

- ^ "Main Page - BlenderWiki". Wiki.blender.org. 2016-11-03. Retrieved 2017-01-22.

- ^ "Blender Stack Exchange". Blender Stack Exchange. Retrieved 2022-02-09.

- ^ "Re-branding Blender". Blender.org. Retrieved March 11, 2014.

- ^ "History". blender.org. 2002-10-13. Retrieved 2012-07-06.

- ^ "Testimonials" (Wayback Machine). Archived from the original on February 21, 2007.

- ^ "blender". Users.skynet.be. Archived from the original on November 27, 2011. Retrieved October 22, 2009.

- ^ "Digital Graphics - Friday or Another Day". Digitalgraphics.be. Archived from the original on 2018-11-08. Retrieved 2018-11-08.

- ^ "The Secret of Kells' nominated for an Oscar!". blendernation.com. 2010-02-04. Archived from the original on 2010-02-05.

- ^ "Blender on the History Channel at BlenderNation". Blendernation.com. 27 September 2006. Retrieved October 22, 2009.

- ^ "Blender Movie Project: Plumíferos". March 8, 2006. Retrieved February 4, 2007.

- ^ "Gecko Animation: Smegging Spaceshipes". Gecko Animation. Archived from the original on 2013-12-24. Retrieved 2013-08-05.

- ^ "Ben Simonds Portfolio - RED DWARF X". Ben Simonds. 4 October 2012.

- ^ "Blender used for Red Dwarf". BlenderNation. October 11, 2012. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- ^ Failes, Ian (May 1, 2014). "Captain America: The Winter Soldier – reaching new heights". fxguide.com. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- ^ Karon, Pavla (7 December 2017). "Max Puliero: "I Use Blender Because It's Powerful, Not Because It's Free"". CG Cookie. Retrieved 2019-06-11.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Death Grips - Inanimate Sensation - YouTube". www.youtube.com. 9 December 2014. Retrieved 2020-07-17.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Blender used at VFX studio, 23 December 2018, retrieved 2021-10-09

- ^ "The Man in the High Castle, Season 2 VFX". Barnstorm VFX.

- ^ "We produced the Visual Effects for Man in the High Castle Season 2". Reddit. 3 February 2017.

- ^ "New Online Exploring Tools Bring NASA's Journey to Mars to New Generation". NASA. 5 August 2015. Retrieved 2015-08-07.

- ^ "Experience Curiosity". NASA's Eyes. Retrieved 2015-08-07.

- ^ "Internet 3D: Take the Curiosity Rover for a Spin Right on the NASA Website". Technology.Org. 11 August 2015. Retrieved 2015-08-12.

- ^ "Khronos Events – 2015 SIGGRAPH". Khronos. 10 August 2015. Retrieved 2015-08-13.

- ^ BSG Web Group. "Cassini". nasa3d.arc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Hardcore Henry – using Blender for VFX". Blender News.

- ^ "Feature length film: Sabogal". BlenderNation. May 1, 2015. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- ^ Richard, Kennedy (July 7, 2016). "Blender Used In Warcraft (2016) Feature Film". BlenderNation. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Sandberg, David F. (November 20, 2016). "The Homemade VFX in Lights Out". YouTube. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Sandberg, David F. (April 4, 2017). "Annabelle Creation Trailer - Behind The Scenes". YouTube. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- ^ "Interview With David F. Sandberg". openvisualfx.com. June 6, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- ^ "Wonder Woman (2017)". artofthetitle.com. 2017-06-21. Retrieved 2017-09-11.

- ^ "Cinderella the Cat, Interview: Alessandro Rak - Director". cineuropa.org. 2017-07-09. Retrieved 2017-09-11.

- ^ World Building in Blender - Ian Hubert, 24 October 2019, retrieved 2022-03-09

- ^ ""Next Gen" - Blender Production by Tangent Animation soon on Netflix! - BlenderNation". BlenderNation. 2018-08-20. Retrieved 2018-09-12.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Blender and Next Gen: a Netflix Original - Jeff Bell - Blender Conference 2018". 2018-11-04. Retrieved 2018-11-08.

- ^ Failes, Ian (2019-11-30). "How the 'I Lost My Body' filmmakers used Blender to create their startling animated feature". befores & afters. Retrieved 2021-10-04.

- ^ "Ubisoft Joins Blender Development Fund to Support Open Source Animation". Ubisoft. 2019-07-22. Archived from the original on 2019-07-23. Retrieved 2019-07-29.

- ^ Nishida, Munechika (2019-08-14). "「やっと3Dツールが紙とペンのような存在になる」エヴァ制作のカラーがBlenderへの移行を進める理由とは?(西田宗千佳)" ["Finally, 3D tools become something like paper and pen" Why Khara, produced Eva, is moving to Blender? (Nishida Munechika)]. Engadget 日本版 (in Japanese). Retrieved 2019-08-15.

- ^ "Blender開発基金への賛同について" [About supporting Blender Development Fund]. Khara, Inc. (in Japanese). 2019-07-30. Retrieved 2019-08-15.

- ^ Blender [@blender_org] (2019-07-24). "The Japanese Anime studios Khara and its child company Project Studio Q sign up as Corporate Silver and Bronze members of Development Fund. They're working on the Evangelion feature animation movie. https://www.khara.co.jp https://studio-q.co.jp #b3d" (Tweet). Retrieved 2019-08-15 – via Twitter.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "Japanese anime studio Khara moving to Blender".

- ^ Foundation, Blender. ""2D Isn't Dead, It Just Became Something Different": Using Blender For Wolfwalkers". blender.org. Retrieved 2021-03-06.

- ^ "New "Maya and the Three" Made With Blender Series Images Released". BlenderNation. 2021-06-16. Retrieved 2021-10-28.

- ^ "Award Winning SPA Studios Looking for Blender TA's and TD's in Madrid, Spain". BlenderNation. 2021-03-24. Retrieved 2021-03-28.

- ^ FAST GREASE PENCIL - Blender.Today LIVE #182, 14 February 2022, retrieved 2022-05-06

- ^ "Warner Bros. Animation on LinkedIn: #hiring #cganimation #warnerbrosanimation". www.linkedin.com. Retrieved 2022-02-15.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "Visual Effects for the Indian blockbuster "RRR"". blender.org. Retrieved 2022-06-30.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "Inklines Across the Spider-Verse (encore) — Blender Conference 2023". Blender Conference 2023 — conference.blender.org. Retrieved 2024-11-26.

- ^ Contreras, Stefaan (2023-06-10). "@scontreras on X". X (Formerly known as Twitter). Retrieved 2024-11-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Foundation, Blender. "My Journey Across the Spider-Verse: from Hobbyist to Hollywood — Blender Conference 2023". Blender Conference 2023 — conference.blender.org. Retrieved 2024-11-26.

- ^ Bricken, Rob (2023-06-05). "Teen Behind Viral Lego Spider-Verse Trailer Recruited to Help Direct Movie". Gizmodo. Retrieved 2024-11-26.

- ^ Blender (2024-10-24). The animation of Flow — Blender Conference 2024. Retrieved 2024-11-26 – via YouTube.

- ^ published, Joe Foley (2024-09-15). "One of year's best animated films was entirely made in Blender". Creative Bloq. Retrieved 2024-11-26.

- ^ "Blender — Open Projects". Blender.org. Retrieved 2019-06-11.

- ^ "Blender Cloud — Open Projects". Cloud.blender.org. Archived from the original on 2020-10-20. Retrieved 2019-06-11.

- ^ a b "Blender Institute Announces Blender Cloud Plans". Blendernation.com. 17 January 2014. Retrieved 2017-01-22.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: Happy Cloud - Project Gooseberry launches on SXSW, 17 March 2014, retrieved 2021-10-26

- ^ Institute, Blender. "Blender Studio and Blender Cloud". Blender Studio. Retrieved 2021-10-26.

- ^ "Blender Cloud V3 - Blog — Blender Cloud". Cloud.blender.org. Retrieved 2017-01-22.

- ^ "Blender Cloud Relaunch". Blendernation.com. 4 June 2014. Retrieved 2017-01-22.

- ^ "Blender / CloudRig". GitLab. Retrieved 2021-10-26.

- ^ Institute, Blender. "Kitsu add-on for Blender". Blender Studio. Retrieved 2021-10-26.

- ^ Institute, Blender. "Contact Sheet Add-on". Blender Studio. Retrieved 2021-10-26.

- ^ "blender-purge · rBSTS". developer.blender.org. Retrieved 2021-10-26.

- ^ "shot-builder · rBSTS". developer.blender.org. Retrieved 2021-10-26.

- ^ Institute, Blender. "Tools". Blender Studio. Retrieved 2021-10-26.

- ^ "Blender Studio Tools · rBSTS". developer.blender.org. Retrieved 2021-10-26.

- ^ Institute, Blender. "Blender Studio and Blender Cloud". Blender Studio. Retrieved 2021-10-25.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "Blender Development Fund". Blender Development Fund. Retrieved 2021-10-20.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "Epic Games supports Blender Foundation with $1.2 million Epic MegaGrant". blender.org. Retrieved 2021-10-20.

- ^ "NVIDIA joins Blender Development Fund". BlenderNation. 2019-10-07. Retrieved 2021-10-20.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "Microsoft joins the Blender Development Fund". blender.org. Retrieved 2021-10-20.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "Apple joins Blender Development Fund". blender.org. Retrieved 2021-10-20.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "Unity joins the Blender Development Fund as a Patron Member". blender.org. Retrieved 2021-10-20.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "Intel signs up as Corporate Patron". blender.org. Retrieved 2021-12-22.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "New Patron member: Decentraland". blender.org. Retrieved 2021-12-22.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "AWS joins the Blender Development Fund". blender.org. Retrieved 2021-10-20.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "Facebook joins the Blender Development Fund". blender.org. Retrieved 2021-10-20.

- ^ "AMD joins NVIDIA as Blender Development Fund patron". BlenderNation. 2019-10-23. Retrieved 2021-10-20.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "Adobe joins Blender Development Fund". blender.org. Retrieved 2021-10-20.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "Donations". blender.org. Retrieved 2021-10-20.

- ^ "Home - Blender ID". Blender.org. Retrieved 2017-01-22.

- ^ "Blender - Open Data". Blender.org. Retrieved 2021-04-06.

- ^ "Org:Foundation/BlenderNetwork - BlenderWiki". archive.blender.org. Retrieved 2021-10-25.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "Sunsetting Blender Network in 2021". blender.org. Retrieved 2021-10-25.

- ^ "Blender Store". Retrieved 2021-10-20.

- ^ "About". Blender Extensions. Archived from the original on 2024-07-16. Retrieved 2024-07-17.

- ^ "Index of /source/". blender.org. Retrieved October 13, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Foundation, Blender. "Blender's History".

- ^ "Blender 2.40". blender.org. Archived from the original on March 4, 2007. Retrieved December 23, 2005.

- ^ "3D-Software Blender 2.46 zum Download freigegeben". heise.de (in German). 20 May 2008. Retrieved May 20, 2008.

- ^ "Blender 2.48". blender.org. Archived from the original on January 20, 2009. Retrieved December 25, 2008.

- ^ "Blender 2.49". blender.org. Archived from the original on June 11, 2009. Retrieved June 21, 2009.

- ^ "Blender 2.57". blender.org. Archived from the original on October 30, 2013. Retrieved April 13, 2011.

- ^ blenderfoundation (2011-07-09). "Blender 2.58 release notes". blender.org. Retrieved 2019-01-14.

- ^ blenderfoundation (2011-07-09). "Blender 2.58a update log". blender.org. Retrieved 2019-01-14.

- ^ "Dev:Ref/Release Notes/2.61 - BlenderWiki". archive.blender.org. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "2.66". blender.org. Retrieved 2024-04-01.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "2.67". blender.org. Retrieved 2024-04-01.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "2.68". blender.org. Retrieved 2024-04-01.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "2.69". blender.org. Retrieved 2024-04-01.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "2.70". blender.org. Retrieved 2024-04-01.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "2.71". blender.org. Retrieved 2024-04-01.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "2.72". blender.org. Retrieved 2024-04-01.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "2.73". blender.org. Retrieved 2024-04-01.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "2.74". blender.org. Retrieved 2024-04-01.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "2.75". blender.org. Retrieved 2024-04-01.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "2.76". blender.org. Retrieved 2024-04-01.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "2.77". blender.org. Retrieved 2024-04-01.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "2.78". blender.org. Retrieved 2024-04-01.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "2.79". blender.org. Retrieved 2024-04-01.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "2.80". blender.org. Retrieved 2024-04-01.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "2.81". blender.org. Retrieved 2024-04-01.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "2.82". blender.org. Retrieved 2024-04-01.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "2.83 LTS". blender.org. Retrieved 2020-06-10.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "2.90". blender.org. Retrieved 2021-10-02.

- ^ "2.91". blender.org. Retrieved 2020-11-26.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "2.92". blender.org. Retrieved 2021-02-27.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "2.93 LTS". blender.org. Retrieved 2024-04-01.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "3.0". blender.org. Retrieved 2024-04-01.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "3.1". blender.org. Retrieved 2024-04-01.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "3.2". blender.org. Retrieved 2024-03-29.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "3.3 LTS". blender.org. Retrieved 2024-03-29.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "3.4". blender.org. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "3.5". blender.org. Retrieved 2024-03-27.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "3.6 LTS". blender.org. Retrieved 2024-03-27.

- ^ "Blender 4.0 release notes".

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "4.1". blender.org. Retrieved 2024-03-27.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "4.2". blender.org. Retrieved 2024-07-16.

- ^ "Reference/Release Notes/4.2 - Blender Developer Wiki".

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "4.3". blender.org. Retrieved 2024-11-19.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "Blender 4.3 Release Notes". blender.org. Retrieved 2024-10-24.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "4.4 Planned Release Schedule". blender.org. Archived from the original on 2024-10-24. Retrieved 2024-10-24.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "Blender 4.4 Release Notes". blender.org. Retrieved 2024-10-24.

- ^ Foundation, Blender. "4.5 Planned Release Schedule". blender.org. Archived from the original on 2024-11-16. Retrieved 2024-11-16.

- ^ "Download – blender.org – Home of the Blender project – Free and Open 3D Creation Software". Blender Foundation. Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- ^ "FreeBSD Ports: Graphics". FreeBSD. The FreeBSD Project. March 16, 2018. Archived from the original on September 20, 2020. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ^ "Requirements".

- ^ "What You Need to Get Started with Blender". 17 December 2023.

- ^ "System Requirements". Blender.org. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ^ "Index of /demo/android/". download.blender.org. Retrieved 2020-09-23.

Further reading

[edit]- Van Gumster, Jason (2009). Blender For Dummies. Indianapolis, Indiana: Wiley Publishing, Inc. p. 408. ISBN 978-0-470-40018-0.

- "Blender 3D Design, Spring 2008". Tufts OpenCourseWare. Tufts University. 2008. Archived from the original on July 20, 2011. Retrieved July 23, 2011.

- "Release Logs". Blender.org. Blender Foundation. Retrieved July 23, 2011.

External links

[edit]- 1995 software

- Free 2D animation software

- Free 3D animation software

- 3D rendering software for Linux

- 3D modeling software for Linux

- AmigaOS 4 software

- Blender Foundation

- Computer-aided design software for Linux

- Cross-platform free software

- Free software for BSD

- Free software for Linux

- Free software for Windows

- Free software for macOS

- Formerly proprietary software

- Free computer-aided design software

- Free software programmed in C

- Free software programmed in C++

- Free software programmed in Python

- Global illumination software

- Haiku (operating system)

- IRIX software

- MacOS graphics-related software

- MorphOS software

- Motion graphics software for Linux

- Portable software

- Software that uses FFmpeg

- Technical communication tools

- Visual effects software

- Windows graphics-related software