Donatello

Donatello | |

|---|---|

Donatello, an imagined 16th-century portrait by an unknown artist[1] (The former attribution to Paolo Uccello is no longer accepted.) | |

| Born | Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi c. 1386 |

| Died | 13 December 1466 (aged 79–80) Republic of Florence |

| Nationality | Florentine |

| Known for | Sculpture |

| Notable work | Saint George David Equestrian Monument of Gattamelata |

| Movement | Early Renaissance |

Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi (c. 1386 – 13 December 1466), known mononymously as Donatello (English: /ˌdɒnəˈtɛloʊ/;[2] Italian: [donaˈtɛllo]), was an Italian sculptor of the Renaissance period.[a] Born in Florence, he studied classical sculpture and used his knowledge to develop an Early Renaissance style of sculpture. He spent time in other cities, where he worked on commissions and taught others; his periods in Rome, Padua, and Siena introduced to other parts of Italy the techniques he had developed in the course of a long and productive career. His David was the first freestanding nude male sculpture since antiquity; like much of his work it was commissioned by the Medici family.

He worked with stone, bronze, wood, clay, stucco, and wax, and used glass in inventive ways. He had several assistants, with four perhaps being a typical number.[citation needed] Although his best-known works are mostly statues executed in the round, he developed a new, very shallow, type of bas-relief for small works, and a good deal of his output was architectural reliefs for pulpits, altars and tombs, as well as Madonna and Childs for homes.

Broad, overlapping, phases can be seen in his style, beginning with the development of expressiveness and classical monumentality in statues, then developing energy and charm, mostly in smaller works. Early on he veered away from the International Gothic style he learned from Lorenzo Ghiberti, with classically informed pieces, and further on a number of stark, even brutal pieces. The sensuous eroticism of his most famous work, the bronze David, is very rarely seen in other pieces.

Working and personal life

[edit]All accounts describe Donatello as amiable and well-liked, but rather poor at the business side of his career.[3] Like (not only) Michelangelo in the next century, he tended to accept more commissions than he could handle,[4] and many works were either completed some years late, handed to other sculptors to finish, or never produced. Again like Michelangelo, he enjoyed steady support and patronage from the Medici family.

All sources agree that he carved stone and modelled clay or wax for bronzes very quickly and confidently, and art historians feel able to distinguish his hand from that of others, even within the same work. Italian Renaissance sculptors nearly always used assistants, with the master often giving parts of a piece over to them, but Donatello, who would perhaps not have been good at managing a large workshop like that of Ghiberti,[5] seems to have had at most times a relatively small number of experienced assistants, some of whom became significant masters in their own right. The technical quality of his work can vary, especially in bronze pieces, where casting faults may occur; even the bronze David has a hole under his chin, and a patch on his thigh.[6]

Donatello certainly made drawings, probably especially for reliefs. In the case of his stained glass designs and perhaps other works these were his whole contribution. Vasari claimed to have several in his collection, which he praised highly: "I have both nude and draped figures, various animals which astound anyone who sees them, and other beautiful things..".[8] But very few, if any, surviving drawings are now accepted as probably by his own hand, and these are strong and lively sketches with figures, such as the three in its collections that the French government still attributes to Donatello himself.[9]

A story told both by Vasari and the earlier Pomponio Gaurico says that he kept a bucket containing money hanging on a cord from the ceiling of his workshop, from which those around could take if they needed it.[10] A tax return from 1427, near the peak of his career, shows a much lower income than Ghiberti's for the same year,[11] and he seems to have died in modest circumstances, although this may not have been of concern to him;[12] "he was very happy in his old age" according to Vasari.[13]

Early life

[edit]Donatello was born in Florence, probably in 1386, based on his own later statement in his catasto tax declaration; he claimed to be 41 years old in July 1427.[14] He was the son of Niccolò di Betto Bardi, who was a "wool-stretcher" (tiratore di lana) and member of the Florentine Arte della Lana, the wool workers guild, which probably provided a good income.[15]

Donatello's actual surname was therefore Bardi, but if he was related to the well known Bardi family of bankers, it seems to have been rather distantly.[16] The banker Bardis were still wealthy and powerful, despite the default of Edward III of England in 1345 having caused the failure of their bank. After Contessina de' Bardi married Cosimo de' Medici around 1415, any connection he had might still have been useful to Donatello. However, Donatello's father did have a connection with the powerful Buonaccorso Pitti, whose diary records a fight in Pisa in 1380 in which Niccolò intervened, giving Pitti's opponent a fatal blow.[17]

Vasari's claim that Donatello was raised and educated in the house of the prominent Martelli family is probably baseless, and given for literary, even political reasons. They were certainly later keen patrons of Donatello, and also commissioned work from Vasari himself.[18]

Early career

[edit]Donatello's first appearance in any documentary records is unpromising; in January 1401, at the age of about 15, he was accused in Pistoia, 25 miles from Florence and then controlled by it, of hitting a German with a stick, drawing blood.[19] He was probably there with his father, who had an official job in Pistoia at the time, while Buonaccorso Pitti was the Captain, or governor.[20] While there Donatello appears to have befriended, and perhaps worked with, Filippo Brunelleschi, who was some ten years older (born in 1377), and although not yet a master goldsmith, working on silver figures for an altar in Pistoia Cathedral. What experience Donatello had to assist him, if that was what he was doing, is unclear.[21]

Both Donatello and Brunelleschi returned to Florence in early 1401, in time for Brunelleschi to take part in the famous competition for the Baptistery doors, often seen as the start of Florentine Renaissance sculpture.[22] Seven sculptors were invited to submit trial panels, for which they were paid; Vasari's Life of Brunelleschi wrongly claims that Donatello was one of them, but they were all more experienced figures. Following Vasari and Brunelleschi's biographer Antonio Manetti, the unexpected result declared by the 34 judges was that the entries by two young Florentines, Lorenzo Ghiberti and Brunelleschi, were the best. An attempt was made to get the two to share the commission, but amid bitter recriminations that lasted for years, this failed and Ghiberti was given the whole commission.[23] Ghiberti himself on the other hand (and the only contemporary voice) claimed in his Commentarii that the vote went unanimously for him, including the competing artists.[24]

Any part played by the adolescent Donatello, presumably assisting Brunelleschi with his trial piece, is unknown. After the final result in late 1402, or early 1403, they seem to have left for Rome together, staying until at least the next year, to study the artistic and architectural remains left by Ancient Rome, then very abundant, though for the most part still buried.[25] They were very early in this effectively archaeological pursuit, which included measuring remains, and hiring labourers to excavate. The main source for this period is the biography of Brunelleschi by Antonio Manetti (1423–1497), who knew both men, but it was written after their deaths in the 1470s.[26]

Vasari just repeats a shorter version of Manetti's account, according to which both men were able to support themselves by jobs for Roman goldsmiths, which probably represented important training for Donatello. Perhaps they were also able to sell excavated sculptures.[27] Brunelleschi subsequently became a highly important architect, while Donatello began his career in sculpture.

Donatello is recorded as working as an apprentice, and for the last few months on a salary, in the studio of Lorenzo Ghiberti in 1404–1407,[28] apparently working on the workshop's main project, the bronze doors of the Florence Baptistery,[29] and from 1406 on he began stone carving at the cathedral for the Porta della Mandorla on its north side, a large project that was still some years from completion. He was paid in November 1406 for a figure of a prophet on the door, most probably the one for the left pinnacle (now in the Museo dell' Opera del Duomo, the cathedral museum).[b] Giovanni d'Ambrogio, whose work, according to Kreytenberg, "provided a decisive impetus for the emergence of Renaissance sculpture", has been described by Manfred Wundram as the "true mentor of Donatello".[30]

Early statues for Florence

[edit]

Cathedral

[edit]By early 1408 Donatello had acquired sufficient reputation to be given the commission for a life-size prophet for the cathedral, to be paired with another by Nanni di Banco, a brilliant sculptor of Donatello's age, who seems to have been both a rival and friend.[31] In the end they were not placed as intended, probably because they appeared too small from far below, and the Donatello appears to be lost.[32]

From now on he received a series of commissions for full-size statues for prominent public locations. These are now among his most famous works, but after about 1425 he produced few sculptures of this type. His marble David may date from around this time, or slightly later, perhaps 1412.[33] He was commissioned to rework it in 1416, the cathedral surrendering it to the republic, who placed in the seat of government, the Palazzo Vecchio.[34] It was "one of the early cases in monumental sculpture where he is portrayed as a youth", rather than the King of Israel, and "teeters between the Gothic and Renaissance worlds".[35]

In 1409–1411 he executed the colossal seated figure of Saint John the Evangelist, which occupied a niche of the old cathedral façade until 1588, and is now in the cathedral museum. This was placed with the base about 3 metres from the ground, and Donatello adjusts his composition with this in mind; since 2015 it and other cathedral sculptures have been displayed at their original heights.[36]

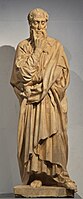

In 1415 the cathedral authorities decided to revive and complete medieval projects, and add eight lifesize marble figures for the niches of the higher levels of Giotto's Campanile adjoining the cathedral, as well as complete a row on the cathedral facade (in which Donatello was not involved). All the figures for the campanile series were removed in 1940, to be replaced by replicas with the originals moved to the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo. They were placed very high, and so were seen from a distance, at a sharp angle, factors which needed allowing for in the compositions, and made "fine detail virtually useless for visual effect";[37] Since 2015 the museum's new displays show this and other statues for the cathedral at the intended original heights.

Donatello was responsible for six of the eight campanile figures, in two cases working with the younger Nanni di Bartolo (il Rosso). The commissions and starts stretched between 1414 and 1423, and while most were completed by 1421, the last of his statues was not finished until 1435.[38] This was the striking Zuccone ("Baldy", or "Pumpkin Head" probably intended as Habakkuk or Jeremiah), the best known of the series, and reportedly Donatello's favourite.[39]

His other statues for the campanile are known as: the Beardless Prophet and Bearded Prophet (both from 1414 to 1420); the Sacrifice of Isaac (with Nanni di Batolo, 1421); il Populano, a prophet not finally finished until 1435.[40]

The visibility of statues high on the cathedral buildings was to remain a concern for the rest of the century; Michelangelo's David was intended for such a place, but proved too heavy to raise and support. Donatello, with Brunelleschi, proposed a large but lightweight solution, and made a prophet Joshua with a brick core, then a modelled layer of clay or terracotta, all painted white. This was put in place on the cathedral some time after 1415, and remained until the 18th century; it was known as the "White Colossus" or homo magnus et albus ("Large White Man").[41]

Orsanmichele

[edit]

Another large-scale sculptural project in the city was the completion of the statues for the niches around the outside of the rectangular Orsanmichele, a building owned by the guilds of Florence, which was in the process of turning itself from a grain market to a church on the ground floor, still with offices above. There were 14 niches around the outside, and each of the main guilds was responsible for one, normally choosing their patron saint. The location had the advantage that the niches were much lower than on the cathedral, with the feet of the statues some three metres above ground level.[42]

Nevertheless, according to a story in Vasari, Donatello had trouble with his first statue for Orsanmichele, a marble St. Mark (1411–1413) for the linen-weavers guild. Viewing the finished statue at ground level, the weavers did not like it. Donatello got them to put it in its niche and cover it up while he worked to improve it. After two weeks under cover, he showed it in position, without having done any work on it, and they happily accepted it.[43] It has a contrapposto pose, with the robe on the leg bearing the weight in straight "vertical drapery folds resembling the flutes of a Doric column."[44] Like most of the Orsanmichele statues, this has been moved to the museum inside, and replaced by a replica.

About 1415 to 1417 he completed the marble Saint George for the Confraternity of the Cuirass-makers or armourers; the important relief on the base is discussed below, and was slightly later.[45] Because of a staircase on the other side of the wall, the niche is shallower than the others, but Donatello turns this to his advantage, pushing the figure forward into space, and with the "anxious look" on the face suggesting alertness or prontezza, "the quality above all others singled out for praise in the successive Renaissance eulogies of the work". Holes and the shape of a hand suggest that the figure was originally fitted with a wreath or helmet on his head, and carried a sword or lance; the client would have been able to supply these pieces in bronze.[46]

The gilt-bronze Saint Louis of Toulouse dates to some years later, 1423–25. It is now in the museum of the Basilica di Santa Croce, having been replaced in 1460 by the bronze Incredulity of Saint Thomas by Verrocchio. It is technically very unusual, as it was built up from a number of sections cast and gilded separately, necessitated by the difficulty of fire-gilding a whole over-life size figure. The collaboration with Michelozzo may have begun with this piece,[47] and 1423 marks the beginning of Donatello's documented work in bronze, with three recorded commissions that year: the Saint Louis, a reliquary bust of Saint Rossore, and the relief for the Siena Baptistery discussed below.[48] Michelozzo had great experience with bronze, and no doubt helped with the technical aspects, and Donatello took to the medium very quickly.[49]

Elsewhere

[edit]In 1418 the Signoria commissioned a large and imposing figure of Florence's heraldic lion, the Marzocco for the entrance to a new apartment at Santa Maria Novella built for a rare visit by the pope; in the event he did not finish it in time.[50] It was later placed in the Piazza della Signoria, where there is now a replica, with the original in the Bargello Museum.

Before about 1410 he made the painted wooden crucifix now in Santa Croce,[51] which features in a famous story in Vasari. It portrays a very realistic Christ in a moment of agony, eyes, and mouth partially opened, the body contracted in an ungraceful posture. According to the story, Donatello proudly showed it to Brunelleschi, who complained it made Christ look like a peasant,[52] at which Donatello challenged him to do something better; he then produced the Brunelleschi Crucifix. At the time Brunelleschi's more classical figure was probably considered to have won the contest, but modern tastes may dispute this.[53]

-

The "marble David", 1408–09 and 1416, Bargello

-

Saint Mark, Orsanmichele, 1411–13

-

The "Beardless Prophet" for the campanile, 1416–18, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo

-

Bearded Prophet, for the campanile, 1418–20, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo

-

Jeremiah, for the campanile, 1423–26, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo

-

Il Zuccone, for the campanile, 1426–c. 1427 and 1435–36, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo

-

Saint Louis of Toulouse and its (copied) niche for Orsanmichele, 1423–25

-

The Marzocco, 1418–20, Bargello

Stiacciato relief style

[edit]

Donatello became famous for his reliefs, especially his development of a very "low" or shallow relief style, called stiacciato (literally "flattened-out"), where all parts of the relief are low. This contrasted with the developing technique of other sculptors who included very high and low relief in the same composition, with Ghiberti's "Gates of Paradise" doors (1424-1451) for the Florence Baptistery a leading example.[54]

Donatello's "first milestone" in the technique is his marble Saint George Freeing the Princess on the base of his Saint George for Orsanmichele. The figures project slightly forward, but "by skilful overlaps are brought back into a tightly-stretched unified skin-plane which is scarcely broken in surface relief to suggest a deep, though not limitless, space".[55] The relief does not provide a "completely coherent system of perspective" (nor did any Italian work for some five or six years after), but the arcaded hall on the right represents a partial scheme of perspective.[56]

His next major development in this direction was in bronze, still a relatively new medium for him. Ghiberti had been involved from 1417 for a project for the font at the Siena Baptistery; it seems to have been his idea to have six bronze, rather than marble, reliefs, and these were allocated to him, Jacopo della Quercia, and a local father and son team. By 1423 Ghiberti had not even started work, and one relief, The Feast of Herod was given to Donatello instead (the overall subject was the life of John the Baptist).[57]

This is placed low, the bottom at about the level of the viewer's knee, and the relief allows for that. The composition has figures in three receding planes defined by the architecture. At left Herod recoils in horror as he is presented with John the Baptist's head on a platter; to the right of centre Salome is still dancing. In a space behind musicians are playing, and beyond them John's head is presented to two figures, one presumably Herodias. It does not represent a full one-point perspective scheme, as there are two vanishing points, perhaps intended to create subliminal impressions of tension and disharmony in the viewer, reflecting the grisly subject.[58]

Other stiacciato reliefs include The Assumption of the Virgin in the wall-tomb in Sant'Angelo a Nilo, Naples, (1426-1428, see below), the Madonna of the Clouds and Pazzi Madonna, both c. 1425−1430 and domestic pieces respectively with and without a carved background, The Ascension with Christ Giving the Keys to Saint Peter (1428–30), for an unknown location but in the Medici collection by the end of the century, and a small Virgin and Child (perhaps 1426, probably by his workshop).[60]

At all times Donatello and his workshop made more conventional reliefs, at a variety of depths and sizes, and in different materials.[61]

Partnership with Michelozzo

[edit]Around 1425 Donatello entered into a formal partnership with Michelozzo, who is mainly remembered as an architect, but was also a sculptor, especially of smaller-scale works in metal. He had trained with the mint making dies for coins, where he still had a salaried position. Michelozzo was the younger by about ten years, and they had probably known each other for years. Michelozzo wanted to extract himself from an arrangement with Ghiberti, and Donatello had too much work, and was poor at organizing a workshop, at which Michelozzo seems to have excelled. Both had very good relations with the Medici family and so their powerful supporters. The partnership was very successful, and was renewed until it had lasted for nine years, when a dispute that was mostly the fault of Donatello ended it.[62]

The partnership's combination of skills in monumental sculpture and architecture made it well qualified to take on elaborate wall tombs. From 1425 to 1428, they collaborated on the Tomb of Antipope John XXIII in the Florence Baptistery; the executors were Giovanni de' Medici and Medici supporters. Donatello made the recumbent bronze figure of the deceased, and Michelozzo, with assistants, the several figures in stone. The tomb, elegantly integrating a variety of elements into a narrow vertical space, in a classicizing style, made a great impact and "became the model for the Quattrocento wall-tomb whenever an elaborate or particular impressive expression was wanted" with variations found well into the next century.[63]

After his death in 1427, the partnership took on the funerary monument of Cardinal Rainaldo Brancacci, a Medici ally, at the church of Sant'Angelo a Nilo in Naples. The work was done at Pisa on the coast, and the pieces shipped south. A donkey was purchased to help with transport, and in 1426 Donatello had bought a boat to ship marble from Carrara to Pisa. Donatello's personal contribution was probably limited to the Assumption relief discussed above.[64] Finishing in 1429, for the font at the Baptistery of San Giovanni, Siena, apart from the relief of The Feast of Herod (discussed above), he made small bronze statues of Faith and Hope, and three small bronze spiritelli, naked winged putti-like figures, classical in inspiration, and highly influential on later art.[65]

Images of the Virgin and Child, mostly for homes, had long been a staple for Italian painters, and becoming affordable ever lower down the income scale. Now sculptors were producing them as reliefs, in a variety of materials, and with the cheaper terracotta or plaster ones often painted. The attribution of the large numbers of such images is often difficult, especially as the style of Donatello and contemporaries such as Ghiberti continued to be used for them for a long time.[66]

Another type of work for sculptors was coats of arms and other heraldic pieces for the outsides of the palazzi of the great families of the city, of which Donatello made a number. Donatello also restored antique sculptures for the Palazzo Medici.[67]

The breakup of the partnership with Michelozzo seems to have been partly precipitated by Donatello's delays in doing his part in the commission for an exterior pulpit for Prato Cathedral; highlights in the year at Prato, close to and controlled by Florence, were when the city's famous relic, the Girdle of Thomas (Sacra Cintola), thought to be the belt the Virgin Mary dropped to Thomas the Apostle as she rose in the air during her Assumption, was displayed to the population from a high pulpit. This took place five times every year, one coinciding with a trade fair that was important for the city's economy. The commission began in 1428, but Donatello did not begin work on his allotted areas for years, despite relentless chasing by the Prato authorities, and finally Cosimo de' Medici.[68]

Donatello's reliefs of dancing children for the pulpit, "a veritable bacchanalian dance of half-nude putti, pagan in spirit, passionate in its wonderful rhythmic movement",[69] were finally delivered in 1438, and it seems that though designed by Donatello, perhaps using his first idea for the Florence cantoria frieze (see below), they are not believed to have actually been carved by him. The Prato authorities were unhappy, and the ten years it had taken to get them finished seems to have strained relations with Michelozzo, and the partnership was not renewed in 1434. The two remained on amicable terms, and were to collaborate later. The pulpit reliefs are now replaced by replicas, with the rather weathered originals displayed inside the cathedral.[70]

A factor in the delay was probably Donatello's travelling, which increased from about 1430, after a long period of steady work and residence in Florence after his return from Rome in about 1404. In 1430 he worked with Brunelleschi at Lucca on the construction of a defensive dyke and wall, and later in the year visited Pisa, Lucca again and finished the year in Rome, where he spent much of his time until 1433. Some of this travel was to see antiquities, and political difficulties had greatly reduced the flow of commissions in Florence.[71]

Michelozzo was also with Donatello in Rome for some of the time, but the few products there of the visits lead art historians to describe the visits as mainly resulting in studying classical works. It is not clear whether anything was actually made there, or executed in Florence and shipped down. There was probably a large papal commission in view, but if so, nothing resulted.[72] The main surviving piece is a tabernacle surround for Saint Peter's in marble relief, 228 cm (89.7 in) high, and now in the museum there. The main figurative sections are a stiacciato panel with the Entombment of Christ, and a total of sixteen child-angels at various points in the classicising architectural framework. This "first clearly defines the Early Renaissance wall-tabernacle type" and was very influential.[73]

There was also the old-fashioned tomb slab for the cleric Giovanni Crivelli in Santa Maria in Aracoeli, which might well not be attributed to Donatello if he had not signed it. It is not clear whether a workshop was opened in Rome, or if these were carved in Florence and shipped down.[74]

It has been speculated that the visits led to meetings between Donatello and Leon Battista Alberti, then in Rome, and perhaps writing his De Statua. There may have been mutual influence, and Donatello seems to have returned from Rome with an interest in a modular system of human proportions. The bronze David uses proportions very close to those Alberti recommends.[75]

Children, putti and spiritelli

[edit]

In the 1430s and 1440s Donatello made many sculptures of young children dancing, as well as putti (cherubs) and a variant of these traditionally called spiritelli ("imps" or "sprites"). Putti were not new in Italian sculpture, but were given a rather unusual prominence by Donatello.[76]

Some early examples are three out of a group of six freestanding bronze spiritelli on the cover for the font of the Siena Baptistery (1429), standing over his earlier relief of the Feast of Herod discussed above. One dances and two play musical instruments. They have been said to be "the first true free-standing figurines of the Renaissance" and were enormously influential, expressing "what was at the heart of the Renaissance—the classical reborn into the Christian".[77]

His most famous work in this genre is his relief frieze for the cantoria or singing gallery of Florence Cathedral. There are two of these galleries rather high on the walls of the nave. Luca della Robbia had been given the commission for the first in 1431, and Donatello for the second in 1433, with his contract promising 20% higher payment if his were more beautiful than della Robbia's.[78]

They develop the style of the Prato pulpit reliefs,[79] the figures "primarily symbols of Dionysiac abandon, and the childish character of their bodies is forgotten in our sense of their liberated animal life. If in a photograph we cover their heads our first glance reveals a Bacchic sarcophagus more intricate and vigorous than anything in antique art; and only on looking more carefully are we aware of their fat tummies and chubby legs".[80]

Six spiritelli in animated conversation crowd at the top of the large classical frame of his Cavalcanti Annunciation in Santa Croce, Florence, made for a brother in law of the Medici, c. 1436-1438.[81]

The remarkable bronze statue called the Amore-Attis, perhaps from the early 1440s, has one foot in the world of the spiritelli and the other in the sensuous eroticism of the bronze David. The figure has wings and a tail, stands on a snake, and has a variety of classical attributes, too many for a simple identification. He wears leggings that emphasize rather than hide his private parts.[82] In the 17th century it was taken to be a work of antiquity, despite a clear description of it by Vasari.[83]

Bronze David

[edit]

Donatello's bronze David, now in the Bargello museum, is his most famous work, and the first known free-standing nude statue produced since antiquity. It is conceived fully in the round, independent of any architectural surroundings, and nearly at life-size.[84]

Although the commission is not documented, the statue is first recorded placed on a column in the courtyard of the newly-built Palazzo Medici at a wedding in 1469,[85] but it probably pre-dates the start of that building in 1444. It was most likely commissioned by Cosimo de' Medici for the older Medici palace on the same street, probably between 1434 and 1440, after Donatello returned from Rome and Cosimo from exile.[86]

David was well-established as a symbol of the Republic of Florence, victorious in defence against larger surrounding powers, with at this period the Duchy of Milan the most threatening. Though the statue certainly was intended to convey this meaning, it also has a sensuous and erotic power that was original.[87] The many previous Florentine images of David, like Donatello's stone David of about 1408–09, showed him clothed;[88] here he wears only a hat and boots which, as with the Amore-Attys, serve only to accentuate his nudity.[89]

Donatello's "innovation ... is the transformation of the King of Israel into a young Greek god", in "a work of almost incredible innovation, which nothing else in the art of the time leads us to anticipate ...during the rest of the century in continues to be far beyond the current of contemporary taste."[90] The figure shows "a real boy whose chest was narrower and flank less rounded than the Greek ideal", and the "waist is the centre of plastic interest, from which radiate all the other planes of the body", which became the norm in Renaissance nude sculpture.[91]

One foot rests casually on the severed head of Goliath, giving the figure a contrapposto pose. The feathers of Goliath's helmet crest brush against the inside of David's thigh, in a further sensuous touch. The David and the Amore-Attis supplement various pieces of contemporary gossip to suggest Donatello's sexual interests.[92]

It seems likely that Donatello's homosexuality was well known, and tolerated and protected by the Medici and so others.[93] The main evidence comes from anecdotes in the Detti piacevoli, a large collection of celebrity gossip probably compiled around 1480 (but not published until 1548), perhaps by the humanist and poet Angelo Poliziano (1454–1494), a Medici insider as tutor to Lorenzo's children.[94] These tell of Donatello surrounding himself with "handsome assistants" and chasing in search of one that had fled his workshop.[95]

He was said to hire especially beautiful boys, and "stained" them (probably meaning make-up) so that no one else would find them pleasing; when one assistant left after a quarrel, they made up by "laughing" at each other, a slang term for sex.[96] However, no detail is known with certainty about his private life, and unlike many artists (for example Sandro Botticelli) there are no recorded denunciations for sodomy in the Florentine archives, though these are incomplete.[97][98]

Wooden statues

[edit]

Wood was still used for crucifixes for its lightness. It was also cheap and convenient for carrying it on liturgical processions. Donatello's early crucifix for Santa Croce has lowerable arms for this purpose. Wooden sculptures were almost always painted and partly gilded (as terracotta and even marble and bronze often were).

When a Florentine confraternity in Venice commissioned a statue of John the Baptist, patron saint of Florence, still in the Frari Church there, wood was chosen. The statue is probably the only work by Donatello in the city. He usually did not sign his work, except for some commissions destined for outside Florence.[99] The baptist was signed and dated 1438. Before this was revealed in conservation work it had been dated later, after his stay in Padua, according to the idea that Donatello's works became more and more expressive.

The redating of the Saint John had knock-on consequences for a far more celebrated wooden figure, the Penitent Magdalene long in the Florence Baptistery (now Museo dell'Opera del Duomo), where the carving style is comparable. This is "formidably expressive" in a stark style found in Donatello's last years, and had been dated to around 1456,[100] until the date was found on the other figure; it is now dated generally to the late 1430s, or at any rate before Donatello went to Padua.[101]

According to Kenneth Clark, it shows "a female fakir whose small sunken eyes, gazing across the desert, have beheld the vision of God. Her body is no longer of the least importance to her".[102]

In 2020 the painted wooden crucifix of the church of Sant'Angelo in Legnaia, a suburb of Florence, was attributed by the diocese to Donatello, and dated to the 1460s. This is in a simpler style.[103][104][105][106]

The Old Sacristy

[edit]

The Sagrestia Vecchia, as it is now called,[107] of San Lorenzo, Florence was Donatello's last major project before his years in Padua, and forms the only large space almost wholly decorated by him. Opinions have varied as to the success of his scheme ever since. The various parts combine experimentation in some places and conservatism in others, and the whole has failed to achieve the iconic status of the rather similar Pazzi Chapel of a few years later, which perhaps learnt the lessons of the sacristy; Luca della Robbia was the sculptor there.[108]

The sacristy was newly built, designed by Brunelleschi,[109] and the first part completed of a major reconstruction of the church by the Medicis. It combined the functions of a Medici funerary chapel, containing the tomb of Giovanni and his wife under the vesting table for the vestments to be laid out; both are still in place.[110] The exact dates of Donatello's involvement are unclear, but it is usually placed after the return from exile of the Medicis in 1434, and Donatello's departure for Pisa in 1443/44, probably at the end of the 1430s.[111]

Donatello's additions were two pairs of bronze doors with relief panels, and elaborate architectural surrounds for them, and two sets of large relief roundels below the main dome. In the pendentives are four scenes from the life of John the Baptist, and at the top of the purely decorative arches in pietra serena are ones of the Four Evangelists, sitting at large desks on which their attributes perch. These are all in painted stucco, the evangelists mostly white on a now rather muddy blue-grey background, with gold highlights for the halos. Three of the scenes from John's life have many small figures and complicated architectural settings and backgrounds, while the fourth, set on Patmos, has a landscape background. All use a colour scheme of white for the figures, different shades of a terracotta brown for the settings, and the muddy blue-grey for the sky. There are also two large reliefs of pairs of standing Medici patron saints over the doorways, in the same technique and colours. In different places, the stucco was painted both when wet, in a kind of fresco technique, and when dry.[112]

The bronze doors were relatively small and had a stack of five panels on each door, each containing a pair of standing figures on a plain background, a conservative design, possibly influenced by Early Christian art, such as the doors of Santa Sabina in Rome, or consular diptychs. One pair has the Twelve Apostles with other saints making up the numbers, and the other has martyrs, who in most cases cannot be confidently identified. The execution is again uneven, with much probably done by assistants.[113]

The scheme received criticism, by now rather unusual for Donatello, from very early on. The modelling and execution of some of the reliefs was crude, especially the scenes from John's life, and it is often thought that the various added elements distract from the simplicity and harmony of the architecture. The level of detail in the higher reliefs makes them simply hard for the viewer to read from below. According to Antonio Manetti, Brunelleschi's biographer, Donatello did not consult the architect about the additions to the doorways at all, such was his "pride and arrogance".[114]

Filarete, perhaps echoing a comment by Alberti, wrote that the paired figures on the doors looked like fencers; he referred to the apostle doors, though the remark is more fairly applied to the martyrs, most of whom hold thin palm fronds.[115] We do not know how Donatello felt about his finished scheme, but he never used painted stucco again; nor did anyone much else, as within a few years the Della Robbia workshop had perfected painted and glazed terracotta in large pieces, as in the Pazzi Chapel, which was clearly the better technique.[116] The reception of the scheme has been suggested as a factor in Donatello's readiness to abandon Florence for a long period.[117]

In Padua

[edit]Equestrian Monument of Gattamelata

[edit]

In 1443, Donatello was called to Padua by the heirs of the famous condottiere Erasmo da Narni (better known as the Gattamelata, or 'Honey-Cat'), who had died that year. Designing and planning his Equestrian Monument of Gattamelata probably began that year or the next, with the casting mostly done in 1447 or 1448, and the bronze work finished in 1450, although it was not installed on its high stone pedestal until 1453.[118]

Padua was a prosperous city with a university, long under the control of Venice, and generally friendly to the Medici and their artists; Cosimo had almost certainly given his blessing to Donatello's stay.[119] The commission is slightly mysterious; Gattamelata's will specified a relatively modest tomb inside the church, where he was indeed buried. It was unexpected that the Venetian government then ordered a grand public monument for a general who had served them for less than a decade, with rather mixed success.[120] The cost, which must have been enormous, was shared by the Venetian government and the family executors, who handled the works, but it is not clear in what proportions.[121]

A factor may have been a competing commission in nearby Ferrara for an equestrian statue of Niccolò III d'Este, Marquis of Ferrara, another condottiere, by two Florentine sculptors, one a pupil of Donatello. This was slightly smaller than life-size, with the marquis in civilian dress rather than armour. He had died at the end of 1441, and the monument was in place by 1451, before being destroyed by the French in 1796 (a replica is now in place).[122]

The Gattamelata was placed on the square outside the Basilica of St Anthony, a famous pilgrimage church (locally called il Santo), in ground then used as a cemetery.[123] As with other works outside Florence, it was signed.[124] It is the first life-size equestrian statue since antiquity. Donatello may have seen the Regisole at Ravenna, a late Roman example which was another victim of the French, and he certainly knew the Equestrian Statue of Marcus Aurelius (c. 175) in Rome. Donatello's work is strongly classicising, with Roman motifs on the armour and saddle (almost impossible to see in situ), and the horse perhaps derived from the ancient Horses of Saint Mark in Venice. Andrea del Caldiere, a Paduan metalworker, led the team doing the actual casting for this and his other Paduan bronzes.[125] Other equestrian statues, from the 14th century, had not been executed in bronze and had been placed over tombs rather than erected independently, in a public place. This work became the prototype for other equestrian monuments executed in Italy and Europe in the following centuries.

Other work in Padua

[edit]

Donatello was based in Padua for ten years, though he returned to Florence soon after the Gattamelata was finally in place in 1453.[126] He had a studio near the Santo, and several assistants.[127] Decades later Padua was for some time the leading Italian centre for small "table bronzes", which was probably partly a legacy of the stimulus given by Donatello's visit.[128] He did not stay in the city the whole time, and he is documented in Florence at some points, and in 1450 is recorded visiting Mantua and Modena for commissions that never came off; in 1451 he was paid by the Bishop of Ferrara for a work he never finished.[129]

In Padua itself, he completed several works for il Santo, including the first life-sized bronze crucifix (with a wooden cross, 1444–1449), which originally hung well down the nave.[130] In 1895 it was moved to hang over the high altar, for which Donatello had made a bronze enthroned Virgin and Child and six flanking saints, constituting a Holy Conversation, and a total of twenty-one bronze reliefs and one in marble, an Entombment. All these were begun in 1446 and nearly complete by June 1450, though some of the statues seem not quite finished, and other sculptors seem to have done some of the work. The four reliefs of scenes from the Life of Saint Anthony, with highlights in gold, are of a uniform high standard.[131][132]

After more than one rearrangement, the first in 1582, the original disposition of the statues is uncertain, but they were probably closer together, in one row, than they are now, with two now placed on a railing below and forward of the others.[133]

The Madonna and Child Enthroned, between St. Francis and St. Anthony, in bronze (c. 1448), portrays the Christ Child being displayed to the faithful by the Madonna, who wears a crown. The Madonna is neither standing nor sitting on the throne but is portrayed in the act of rising. She is flanked by two saints, Anthony of Padua and Francis of Assisi. Shown at the base of her throne, to each side of the Madonna, are sphinxes, allegorical figures of knowledge. On the throne's back is a relief of the Fall of Man, depicting Adam and Eve.[134]

In Siena

[edit]

Between 1457 and 1461 Donatello was active in and for Siena, though he was now aging, and perhaps mostly contributed designs and modelli rather than carving much himself, at least in stone.[135] In 1457 he had received three large commissions for the city, of which only one reached Siena. Firstly there were bronze doors for the cathedral, of which only a possible trial cast of one panel survives (in the Victoria and Albert Museum); the Sienese may have been unable to fund what would have been a very expensive project.[136]

His bronze Judith and Holofernes is an important late work, which ended in a Medici courtyard in Florence, while his bronze John the Baptist was delivered minus a forearm and is now in Siena Cathedral.[137] Another commission was a large relief Madonna and Child (Madonna delle Grazie) with blue glass inlays in the surround, completed in 1459, with much of the work done by another, perhaps the local Urbano da Cortona, who had been pushed aside to allow Donatello to have the commission.[138]

The signed Judith and Holofernes is in his late, stark, style, showing the killing in progress, with Judith about to strike a second blow. Relief scenes on the triangular base seem to show the drunken feast and revels that preceded the killing, in a final outing for Donatello's sensual mode. However, most of the younger revellers have wings. Donatello used real cloth to give texture in some of the modelling, and perhaps Holofernes' legs were moulded from a live model. It may have been planned as a fountain, as there are spouts at the corners of the base, though there now seems to be no internal plumbing. When the Medici were expelled in 1494 it and the bronze David were moved to the Palazzo della Signoria; the Medici were now intended to be seen as the tyrannical victims rather than the liberating underdogs.[139]

Last years

[edit]

After returning from Siena he remained in Florence until his death in 1466. He was evidently unable to work for a period, of uncertain extent, before his death; Vasari records this, but without any timing.[140] But, with the help of assistants, he embarked on a major project in these years, reliefs that now form two pulpits for San Lorenzo, Florence, the burial place of the Medicis, though it is possible that this was not the function originally intended. They were only assembled in this way in the following century, and the panel sizes vary.[141]

At least the designs of most of these are thought to have by Donatello himself, and the modelling of many parts; the precise attribution of the reliefs remains much discussed. Some appear to have been cast from unfinished modelli, and there is considerable stylistic disparity between panels, and sometimes sections of the same panel. The treatment of the spaces in which the scenes are set is especially varied and experimental, part of "the absolutely uncompromising use of every possible means to express emotion and suffering" that marks these works.[142]

Work involving glass

[edit]

Donatello's inventiveness and search for new effects is shown by his various, mostly novel, uses of glass, a material hardly used in European sculpture before. He was commissioned to design stained glass for Florence Cathedral around 1434, a conventional task, but one usually given to a painter rather than a sculptor.[143] He used glass in tesserae form in the backgrounds of reliefs, including the Prato pulpit and cantoria reliefs,[144] which was an old style, but his background of a network of roundels with glass-covered wax and gold inlays for the terracotta Piot Madonna (Louvre, c. 1440 or later) is original.[145]

His Chellini Madonna (c. 1450, Victoria and Albert Museum) is a round bronze relief, 28.5 cm across, which is cast at an even thickness, meaning that the reverse has an intaglio (concave) image matching the convex relief one on the front. This seems to have been intended to be used as a mould for molten glass and perhaps other materials. Donatello gave it to his doctor and friend Giovanni Chellini in 1456, though it was probably not new at that point.[146]

Portraiture

[edit]

Other than tomb effigies, there is no sculpture by Donatello that is certainly intended to be a portrait. Some of his early statues of prophets for the cathedral were said to use the features of specific individuals.[147] Donatello probably never saw Gattamelata alive, and may not have had any good image to work from; his figure seems to have a generalized "Caesar-like head" and is "no portrait in the usual sense",[148] but an "idealized portrait of brute power".[149]

During Donatello's career, the distinctive Florentine flat-bottomed bust portrait became established and popular among the city's elite, led by the Medici.[150] Donatello is only associated with one example, but this may be the earliest. Niccolò da Uzzano was a significant Medici political associate, as well as a banker and humanist, who died in 1431.[151] The painted terracotta bust portrait of him may have been made using a life- or death mask, presumably not very long after his death, at the latest. He is shown wearing an ancient Roman toga, with "uncompromising realism", but an expression that "exudes sagacious strength and nobility". However the attribution to Donatello, the dating and foremost the quality of the bust itself are disputed.[152]

Vasari's Life

[edit]

Giorgio Vasari's life of Donatello in his Lives of the Artists was mostly researched in the 1540s, around a century after the events he recounts, and contains some clear and significant errors of fact. It fully recognises Donatello's stature as an artist, and lists many works. His knowledge of those in Padua and Siena appears shaky, and may rely on the accounts of others.[153] In his life of Raphael he praises the "beautiful fancy" (bel capriccio) of some figures, which Vasari himself later drew on; but he is evidently unaware that Raphael took them from a Donatello church relief in Padua.[154] He also places Donatello's birth in 1403,[155] some seventeen years after better-informed modern scholars, aware of the record of the assault in 1401,[156] and payments for work going back to 1406.[157]

Vasari, a fierce Florentine patriot, saw Donatello as the start of Florentine dominance in Renaissance sculpture, and traced a line of succession between him and his hero Michelangelo, via the somewhat dubious link of Bertoldo di Giovanni (d. 1491), a pupil of Donatello and in theory Michelangelo's mentor when he ran the informal "garden academy" of Lorenzo de' Medici at the end of his life. Vasari stressed the close ties between Donatello and the Medici, which were certainly important in his life, but also mirrored those Michelangelo and Vasari himself enjoyed.[158]

Legacy

[edit]

Donatello's output was so varied and individual that his influence can be seen in all Florentine sculpture in the 15th century, and well beyond Florence. But he shared important elements of his style, in particular his revival of classical forms and styles, with the other outstanding sculptors of his generation, Ghiberti, Jacopo della Quercia, Luca della Robbia and others. Many younger sculptors assisted him, though his workshop relationships are not very well documented, and recent scholarship has cast doubt on many 19th-century claims (some from Vasari) of other sculptors as "pupils" of Donatello.[159] Regular assistants in Donatello's later years included Bartolomeo Bellano (from Padua) and Bertoldo di Giovanni.[160]

When he died, the "sweet style" that he had helped to produce decades before, dominated in the work of Florentine sculptors; his "late style, with its boldness of imagination and execution, probably overawed them and seemed incomprehensible and inaccessible".[161] Only many years later did Verrocchio and Antonio del Pollaiuolo explore similar expressive effects.[162] His periods in Padua and Siena left behind trained bronze-founders and sculptors who made these cities, especially Padua, significant centres in their own right;[163] indeed, in Padua his presence had a great effect on local painting also.[164] Bartolomeo Bellano was back in Padua by 1469, and remained the leading sculptor there, handing the role over to his pupil Andrea Riccio (c. 1470 – 1532) in due course.[165]

Desiderio da Settignano may have acted as a younger colleague, and was the main other sculptor who could execute shallow reliefs in a way comparable to Donatello. He died in 1464 at just 34, cutting off a very promising career.[166] The shallow relief style was not much used by other sculptors, though Michelangelo's early Madonna of the Stairs (c. 1490) is an essay in it.[167] Michelangelo's David (1501) is both "an ode and a challenge to Donatello".[168]

Collections

[edit]Most of Donatello's major works for churches remain in situ, or moved inside to the church museum. The Bargello in Florence has the main museum collection, including his most famous portable pieces. Hardly any large pieces are outside Italy, but there are many Madonnas and other smaller pieces, often with uncertain attributions. The Victoria and Albert Museum has important shallow reliefs, and the Louvre and Berlin State Museums other pieces; generally the American museums arrived too late on the scene to make many major acquisitions, though they have many pieces with workshop attributions.

Gallery

[edit]Works with architectural elements: tombs and tabernacles

[edit]-

Tomb of Antipope John XXIII, 1423–1425, Baptistry San Giovanni, Florence

-

The tabernacle in St Peter's, Rome, c. 1430–33

-

The high relief Cavalcanti Annunciation, c. 1436–1438

Inventive forms of Madonna and Child

[edit]-

The Bode Madonna, terracotta, c. 1440, Bode Museum, Berlin

-

Piot Madonna, c. 1440

-

Madonna and Child, painted terracotta, c. 1440, Louvre

Bronze sculptures

[edit]-

Crucifix for the Sant'Antonio high altar, Padua, 1443–1449, Museo Antoniano, Padua

-

Statue of St. John the Baptist in the Duomo di Siena, c. 1455

-

Judith and Holofernes, c. 1460

Ancillary works

[edit]-

Coat of arms of the Martelli family, c. 1455, attributed, Bargello, Florence

Selected works

[edit]| Title | Form | Material | Year | Original location | Current location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prophet | Statue | Marble | 1406 | Florence Cathedral, Porta della Mandorla | Florence, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo |

| Santa Croce Crucifix | Crucifix statue | Wood, polychromed | 1407–1408 | Florence, Santa Croce | Florence, Santa Croce, Cappella Bardi di Vernio |

| David, marble | Statue (maybe originally with sling) | Marble | 1408–1409, 1416 | Florence Cathedral, planned for buttress, Palazzo Vecchio (1416) | Florence, Museo nazionale del Bargello |

| John Evangelist | Statue in niche, sitting | Marble | 1408–1415 | Florence Cathedral, façade | Florence, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo |

| Joshua | Statue (5.5 mts high) | Terracotta, whitened | 1410, before | Florence Cathedral, north tribune | disintegrated |

| Saint Mark | Statue in niche | Marble | 1411–1413 | Florence, Orsanmichele | Florenz, Orsanmichele museum |

| St. Louis of Toulouse with tabernacle | Statue in niche | Bronze (gilt-bronze), marble | 1411–1415 | Florence, Orsanmichele | Florence, Santa Croce (since the 1450s) |

| Prophets (unbearded and bearded) | Statues in niche (two of five) | Marble | 1415 and 1418–1420 | Florence Cathedral, Campanile | Florence, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo |

| St. George (with Saint George Freeing the Princess) | Statue and niche with low relief on its base | Marble | 1416, circa | Florence, Orsanmichele | Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello (with niche) |

| Marzocco | Statue on column | Sandstone | 1418–1420 | Florence, Santa Maria Novella, papal apartment | Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello |

| Pazzi Madonna | Relief, low | Marble | 1420, circa | uncertain | Berlin, Bode Museum, Skulpturensammlung |

| Sacrifice of Isaac | Statue in niche (third of five) | Marble | 1421 | Florence, Santa Maria del Fiore, Campanile | Florence, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo |

| San Rossore Reliquary | Bust, reliquary bust | Bronze, gilded | 1422–1427 | Florence, Ognissanti | Pisa, Museo nazionale di San Matteo |

| Jeremiah | Statue in niche (fourth of five) | Marble | 1423, circa | Florence Cathedral, Campanile | Florence, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo |

| Zuccone (Prophet Habakkuk) | Statue in niche (last of five) | Marble | 1423–1425 | Florence Cathedral, Campanile | Florence, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo |

| The Feast of Herod | Relief, low | Bronze | 1423–1427 | Siena, Baptistry of San Giovanni, Baptismal font | Siena, Baptistry |

| Madonna of the Clouds | Relief, low | Marble | 1425−1435 | unknown | Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston[169] |

| Tomb of Cardinal Rainaldo Brancacci: Annunciation relief (all other work by Michelozzo) | relief, low | Marble | 1426–1428 | Naples, Sant'Angelo a Nilo | Naples, Sant'Angelo a Nilo |

| The Ascension with Christ Giving the Keys to Saint Peter | Relief, low | Marble | 1428–1432 | 1492 listed in the collection of Lorenzo de' Medici, until after 1677 in the Salviati family collection[170] | London, Victoria and Albert Museum (Inv. 7629-1861) |

| Dovizia (on the Colonna dell'Abbondanza) | Statue on column | Marble (with a working bell) | 1431 | Florence, Piazza della Repubblica | deteriorated and destroyed in a fall in 1721 (replaced with a version by Giovanni Battista Foggini that was replaced by a copy) |

| David (with head of Goliath), bronze David | Statue on column | Bronze, partly gilded | 1430s–1450s (?) | Florence, Casa Vecchia de' Medici | Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello |

| Pulpit, Cantoria | Pulpit with high reliefs | Marble, mosaic, bronze | 1433–1438 | Florence Cathedral | Florence, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo |

| Pulpit, external | Reliefs | Marble | 1434–1438 | Prato, cathedral | Prato, Cathedral Museum |

| Old Sacristy (doors, lunettes, tondi and frieze) | Reliefs, low | Bronze (doors), polychromed stucco | 1434–1443 | Florence, San Lorenzo | Florence, San Lorenzo |

| Cavalcanti Annunciation | Relief, high, in an aedicula | Pietra serena (Macigno) and terracotta, whitened and gilded | 1435, circa | Florence, Santa Croce | Florence, Santa Croce |

| John the Baptist | Statue | Wood, painted partially gilded | 1438 | Venice, Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari | Venice, Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari |

| Amore-Attis | Statue | Bronze | 1440, circa | Florence | Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello |

| Penitent Magdalene | Statue | Wood and stucco pigmented and gilded | 1440–1442 (?) | Florence | Florence, Museo dell'Opera del Duomo |

| Madonna and Child | Relief, low | Terracotta, pigmented | 1445 (1455) | unknown | Paris, Louvre |

| Gattamelata monument | Equestrian statue (and relief on base) | Bronze, (marble) | 1445–1450 | Padua, Piazza Sant'Antonio | Padua, Piazza Sant'Antonio |

| High altar with Madonna and Child, six statues of saints and four episodes of the life of St. Anthony | Statues (seven) and 21 reliefs | Bronze (and one stone relief) | 1446, after | Padua, Basilica di Sant'Antonio | Padua, Basilica di Sant'Antonio (reconstruction) |

| Judith and Holofernes | Statue group | Bronze | 1457–c. 1461 | Florence, Palazzo Medici, garden | Florence, Palazzo Vecchio |

| John the Baptist | Statue | Bronze | 1455-1457 | Siena, Cathedral | Siena, Cathedral |

| Virgin and Child with Four Angels (Chellini Madonna) | Relief, low, tondo | Bronze, gilded | 1456, before | Florence | London, Victoria and Albert Museum |

| Pulpits, one with scenes of the Passion, one with post-Passion scenes | Reliefs | Bronze | 1460, after | San Lorenzo, Florence | Florence, San Lorenzo |

In popular culture

[edit]Donatello is portrayed by Ben Starr in the 2016 television series Medici: Masters of Florence.[171]

The fictional crimefighter Donatello, one of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, is named after him. Donatello is portrayed by Rhett McLaughlin in the 2014 Epic Rap Battles of History video Artists versus Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, in which he appears working on Gattamelata and is mocked for being less famous than other Renaissance artists.[172]

The minor planet "6056 Donatello" is named after him. At about 13 kilometres across, it is larger than most.[173] The Donatello Multi-Purpose Logistics Module (MPLM) built by the Italian Space Agency, was one of three MPLMs operated by NASA to transfer supplies and equipment to and from the International Space Station. The others were named Leonardo and Raffaello. Donatello is also the name of a new cat of Max Verstappen has adopted.[174]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Though an Italian nation state had yet to be established, the Latin equivalent of the term Italian (italus) had been in use for natives of the region since antiquity. For example in Pliny the Elder, Letters 9.23.

- ^ For the discussion of its identification see Janson 1957, 219-222; Seymour, 51, for the Porta della Mandorla project: 31-35, 51-52 and index; Coonin, 29. Originally Donatello had a commission for two statues that Francesco Caglioti finally identified as an Annunciation group for the tympanum of the portal. An already finished ensemble probably by Giovanni d'Ambrogio was to remain inside the cathedral due to its beauty after it was disposed there while the portal was still under construction. When it was decided nevertheless in 1414 to install these statues at there originally intended place in the tympanum, Donatello was told to rework his already begun annunciation angel into a prophet figure. The statue he was paid for and is now in the cathedral museum, has several remaining features of a Gabriel that are not to be found in prophet figures. First of all prophets were always shown as old men and with a scroll as their main insignia, which Donatello obviously couldn't add anymore. The figure was originally in three-quarter view, turned to the right stepping forward (towards Mary), the parts not supposed to be seen are not worked out, especially around his left foot (See Janson 1957 II, pl. 473a and b). Finally he carries a wreath of leaves on his head which is unusual for a prophet but suits an angel. For the former angel to be installed on the pinnacle some profile of the wall behind it had to be cut off. Nanni di Banco followed him in this accidentally new concept of a prophet figure, but his was suited for the other pinnacle, adding a scroll and not adapting the wreath. - Today the tympanum is decorated with a mosaic of the Annunciation. See Caglioti 2022, 28-32, for the profile cut off the wall see Janson 1957 II, plate 473b (who yet excluded the Young Prophet from Donatello's catalog).

References

[edit]- ^ Unknown master (19 December 2023). "Cinq maîtres de la Renaissance florentine : Giotto, Uccello, Donatello, Manetti, Brunelleschi" [Five masters of the Florentine renaissance]. Le Louvre.

- ^ Wells, John (3 April 2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Pearson Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- ^ Seymour, 50; Coonin, 78; Olson, 73.

- ^ Coonin, 79, 120.

- ^ Coonin, 26-27.

- ^ Olson, 73.

- ^ Coonin, 11-12.

- ^ Vasari, 107.

- ^ But Coonin, 124, feels "there are no surviving drawings convincingly attributed to Donatello".

- ^ Coonin, 9; Vasari, 106.

- ^ Coonin, 78-79.

- ^ Coonin, 10.

- ^ Vasari, 106.

- ^ Coonin, 18.

- ^ Coonin, 17-18.

- ^ Coonin, 18.

- ^ Walker, 11.

- ^ Rubins, 348-352; Vasari, 97, "..brought up from early childhood in the house of Ruberto Martelli", though in this edition the date of birth is corrected (see below); Coonin, 106-107.

- ^ Coonin, 18; Walker, 6, 9.

- ^ Walker, 9.

- ^ Coonin, 18-19; Walker, 4, says Brunelleschi became a master in 1398.

- ^ Seymour, 36: "The story of the competition for the great doors of bronze is perhaps the most familiar in all Early Renaissance art history"; Coonin, 20: "In most art historical narratives the year 1401 introduces the formal beginnings of a revolution in art, the spark of the so-called Renaissance".

- ^ Seymour, 36-40 (lists all 7); Avery, 33-37; Coonin, 20-24; Vasari, 77-78; Hartt, 158-161; Holt, 173-177 gives Manetti's account.

- ^ English translation in: Creighton E. Gilbert: Italian Art. 1400-1500. Sources and Documents. Northwestern University Press, Evanston (Ill.) 1992 (1980), ISBN 0-8101-1034-2, 84.

- ^ For a short survey on antique art that was known at the beginning of the Quattrocento, see Krautheimer, Richard; Krautheimer-Hess, Trude (1982) [1958]. Lorenzo Ghiberti. Princeton Monographs in Art and Archaeology. Vol. 31 (1st Pb. of 2nd ed.). Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 277ff.

- ^ Holt, 178-179 prints Manetti's account.

- ^ Coonin, 24-26; Walker, 26, 30, 34.

- ^ Seymour, 50.

- ^ Coonin, 26.

- ^ Kreytenberg, G. (2012). Hourihane, Colum (ed.). The Grove Encyclopedia of Medieval Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-19-539536-5.

- ^ Seymour, 49-50; Coonin, 28-33.

- ^ Seymour, 52; Coonin, 29-30.

- ^ Seymour, 67. The cathedral records payment in 1412, but this may be for a different figure, now lost or altered.

- ^ Coonin, 60-61; Hartt, 164-165.

- ^ Olson, 48.

- ^ Seymour, 56-57.

- ^ Seymour, 68–70, 69 quoted.

- ^ Seymour, 68.

- ^ Vasari, 101; Coonin, 120-123.

- ^ Seymour, 68.

- ^ Coonin, 34-35; Seymour, 67-68.

- ^ Seymour, 58-64, 71-73, and index; Coonin, 41-47.

- ^ Vasari, 100; Seymour, 59-60.

- ^ Olson, 49.

- ^ Seymour, 64; Coonan,51-52.

- ^ Seymour, 63.

- ^ Seymour, 72-73.

- ^ Seymour, 80.

- ^ Coonin, 84-85.

- ^ Coonin, 61-64.

- ^ Coonin, 37-38. If it is indeed by him, which has been doubted.

- ^ Putting "un contadino in croce", a peasant on the cross.

- ^ Vasari, 97-98; Coonin, 38-41.

- ^ Seymour, 65-66, 79.

- ^ Seymour, 66.

- ^ Seymour, 66.

- ^ Seymour, 77-78; Coonin, 85-86.

- ^ Seymour, 80-81; Coonin, 86-88; Olson, 61-62.

- ^ Olson, 79-82.

- ^ Coonin, 98-104.

- ^ Coonin, 103-104.

- ^ Coonin, 80-83, 97; Seymour, 72, 75-76.

- ^ Coonin, 81-85; Seymour, 75-77, 76 quoted; Olson, 74-75.

- ^ Coonan, 97-100.

- ^ Coonin, 88-93.

- ^ Coonin, 103-104.

- ^ Hesson, Robert (28 July 2019). "Collections and restoration of antiquities – Ancient Monuments". Northern Architecture. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ^ Coonin, 104-105, 109, 112; Seymour, 98.

- ^ Konant.

- ^ Coonin, 104, 112; Seymour, 98; Avery, 78.

- ^ Coonin, 105-106.

- ^ Seymour, 89-90; Coonin, 109.

- ^ Avery, 74, 103-104; Seymour, 90 (quoted); Coonin, 109.

- ^ Coonin, 109.

- ^ Seymour, 90; Coonin, 130-133.

- ^ Coonin, 92-93.

- ^ Coonin, 92-95, 93 quoted.

- ^ Coonan, 112-119.

- ^ Olson, 78-79.

- ^ Clark, 279-280; see also Hartt, 236.

- ^ Coonin, 136-138.

- ^ Coonan, 149-151; Jones, 13.

- ^ Olson, 84.

- ^ Coonin, 141; Konody; Olson, 84; Avery, 82.

- ^ Olson, 83.

- ^ Coonin, 141; Olson, 84; Seymour, 234-235 (note 21). The dating used more typically to be in the 1450s or even later.

- ^ Jones, 1-16; Coonin, 142-145.

- ^ Unlike images of Hercules, who was typically shown naked, Coonin, 141.

- ^ Coonin, 142-147.

- ^ Clark, 48-49.

- ^ Clark, 49-50; see also Avery, 82.

- ^ Coonin, 143-147; Jones, 1-4; Avery, 82.

- ^ Jones, 1-6, 314-315.

- ^ Bowen, Barbara C., “The Collection of Facezie Attributed to Angelo Poliziano”, Bibliothèque d’Humanisme et Renaissance 56, no. 1 (1994): 27–38, JSTOR.

- ^ Jones, 314-315; Michael Rocke, Forbidden Friendships: Homosexuality and Male Culture in Renaissance Florence (see index).

- ^ Summers, Claude (2004). The Queer Encyclopedia of the Visual Arts. Cleis press. p. 97. ISBN 1-57344-191-0..

- ^ Joachim Poeschke, Donatello and His World. Sculpture of the Italian Renaissance, Volume 1, Harry N Abrams, New York 1993, p. ?

- ^ Louis Crompton, Homosexuality and Civilization, Harvard Press, 2003, p. 264.

- ^ Coonin, 151-152.

- ^ Seymour, 144 (quoted); Avery, 91-92, both using the old dating.

- ^ As proposed in Strom, Deborah Phyl, "A new chronology for Donatello's wooden sculpture", Pantheon München, 1980, Vol 38, Num 3, pp 239-248; Coonin, 154-155 (and his note 60).

- ^ Clark, 330.

- ^ Mugnaini, Olga (6 March 2020). "'Quel crocifisso ligneo è di Donatello', la sensazionale scoperta a Firenze". La Nazione (in Italian). Retrieved 26 March 2020..

- ^ "Studioso scopre Crocifisso inedito di Donatello". Adnkronos. Retrieved 26 March 2020..

- ^ Salzano, Marco Pipolo & Guido. "E". QAeditoria.it – QA turismo cultura & arte. Retrieved 26 March 2020..

- ^ "Crocifisso di Donatello nella chiesa di Legnaia, la storia". Isolotto Legnaia Firenze (in Italian). 6 March 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2020..

- ^ Another was added in the early 15th century on the opposite side of the church.

- ^ Coonin, 157-166; Avery, 80-81.

- ^ Coonin, 159. Begun in 1428, with the roof in place by 1428.

- ^ Coonin, 159. The tomb was conceivably designed or partly done by Donatello, as proposed by F. Caglioti in Donatello e i Medici, Florence, 2000.

- ^ Avery, 80; Coonin, 160, 166-167; Seymour, 114.

- ^ Coonin, 159-166; Avery, 80-81; Seymour, 114-115.

- ^ Seymour, 114-115; Coonin, 165-166; Avery, 81.

- ^ Coonin, 161; Seymour, 115.

- ^ Coonin, 161, 165-166; Seymour, 115.

- ^ Coonin, 161-162.

- ^ Coonin, 164-168.

- ^ Seymour, 124-125; Coonin, 171-172.

- ^ Coonin, 169-170.

- ^ Coonin, 171-172; Seymour, 123-124.

- ^ Seymour, 13; Avery, 88.

- ^ Coonin, 173; Seymour, 13, 124.

- ^ Seymour, 124-125; Coonin, 184.

- ^ "OPVS DONATELLI.FLO" ("The work of Donatello the Florentine"), quoted Coonin, 178

- ^ Seymour, 124; Coonin, 173–179.

- ^ Seymour, 125.

- ^ Coonin, 172, 190; Seymour, 125.

- ^ Olsen, 138–140; Wilson, 61; Seymour, 201-203.

- ^ Coonin, 172, 179–-180.

- ^ Coonin, 180-182.

- ^ Coonin, 184–196; Avery, 88–91.

- ^ Janson 1963 II, 162–187.

- ^ Seymour, 125–127 illustrating five possible layouts; Coonin, 184, 196.

- ^ Janson 1963 II, xxiv; the crucifix is shown on plates 242, 243; the Virgin and Child is shown on plates 290–293; Adam and Eve are shown on 295a and b.

- ^ Seymour, 147-148.

- ^ Coonin, 230; Lamentation over the Dead Christ, V&A.

- ^ Seymour, 144-145.

- ^ Coonin, 266-268.

- ^ Olson, 89-90; Coonin, 218-221; Hartt, 285-287.

- ^ Coonin, 239.

- ^ Seymour, 145-146; Coonin, 232-237; Olson, 90.

- ^ Seymour, 145-146, 146 quoted; Coonin, 232-237; Hartt, 287-288; Avery, 94-96; Olson, 90.

- ^ Coonin, 123-125.

- ^ Coonin, 118-119; Seymour, 94; Olson, 78.

- ^ Coonin, 202-203.

- ^ Coonin, 199-202.

- ^ Vasari; Il Zuccone is one of these.

- ^ Seymour, 124.

- ^ Olson, 86 (quoted); Avery, 88 suggests a death mask may have been used, but Gammelata was in his seventies when he died, and the face on the statue looks younger.

- ^ Seymour, 7, 123, 139.

- ^ Treccani biography (not 1433 as Olson, 91 says).

- ^ Olson, 91; the long catalogue entry in The Renaissance Portrait: From Donatello to Bellini, ed. Patricia Lee Rubin, (Metropolitan Museum of Art/Bode-Museum), 2011, 126-128 attributes it to "Workshop of Desiderio da Settignano" from "c. 1450-55", noting that the attribution to Donatello is not recorded before 1745 "when almost all Florentine Quattrocento sculpture was, in confused fashion, ascribed to the Father of the Renaissance" (p. 126). Janson, 1957, 237–40, rejects the attribution to Donatello and hints at Desiderio da Settignano and followers in the 1460s–70s, due to the specific backward tilt of the head; among others he cites Ulrich Middeldorf who denies any artistic quality and speaks of a "complete lack of style in the modeling of the face." (Middeldorf, review of Hans Kauffmann, Donatello, 1935, in: Art Bulletin, 38, 1936, 570ff); lastly indecisive Georges Didi-Huberman, "Torsion, Pathos, Dis-Gratia. Neue kritische Überlegungen zur Büste des Niccolò Uzzano", in: Rowley 2022, 69–83.

- ^ Rubins, 321-322, 340-341.

- ^ Rubins, 322.

- ^ Rubins, 330, in the 2nd edition. This may be a simple typo, as in the life of Brunelleschi he has Donatello (wrongly) entering the 1401-2 competition for the baptistery doors.

- ^ Coonin, 17.

- ^ Coonin, 29.

- ^ Rubins, 352-354; Vasari, 235-236.

- ^ Seymour, 139 (Mino da Fiesole), 140 (Desiderio da Settignano); Coonin, 217.

- ^ Olson, 90; Coonin, 236-237.

- ^ Avery, Chapter 5.

- ^ Avery, 96.

- ^ Avery, 96.

- ^ Hartt, 238.

- ^ Seymour, 202-203.

- ^ Coonin, 212, 240.

- ^ Coonin, 136.

- ^ Coonin, 243-244, 243 quoted.

- ^ Museum page

- ^ Pope-Hennessy 1996, 350.

- ^ "Medici: Masters of Florence". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 24 December 2016.

- ^ ERB (14 July 2014). "Artists vs TMNT. Epic Rap Battles of History". YouTube. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ^ Minor planet center

- ^ "Verstappen has a new four-legged friend: This is the name of his pet". GPblog.com. Retrieved 23 November 2024.

- Avery, Charles, Florentine Renaissance Sculpture, 1970, John Murray Publishing, ISBN 0-7195-1932-2.

- Caglioti, Francesco (ed.) with Laura Cavazzini, Aldo Galli and Neville Rowley (2022). Donatello. The Renaissance. Venice. ISBN 979-12-5463-006-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Clark, Kenneth (1949), The Nude, A Study in Ideal Form, page refs from Pelican edition of 1960.

- Coonin, A. Victor, Donatello and the Dawn of Renaissance Art, 2019, Reaktion Books, ISBN 978-1-78914-130-6.

- Jones, Johnathan, The Loves of the Artists: Art and Passion in the Renaissance, Simon & Schuster, 2013, ISBN 9781849833929.

- Hartt, Frederick, History of Italian Renaissance Art, (2nd edn.) 1987, Thames & Hudson (US Harry N. Abrams), ISBN 0-500-23510-4.

- Holt, Elizabeth Gilmore, ed., A Documentary History of Art, Volume 1: The Middle Ages and the Renaissance, 1981, Princeton (orig. Doubleday 1957).

- Janson, Horst W., The Sculpture of Donatello, 2 Vol., Princeton University Press, Princeton 1957. Archive-URL of the 1963 edition with less plates.

- Konody, Paul George, s:1911_Encyclopædia_Britannica/Donatello, Encyclopædia Britannica, Vol. 8 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press. pp. 406–408.

- Olson, Roberta J. M., Italian Renaissance Sculpture, 1992, Thames & Hudson (World of Art), ISBN 978-0-500-20253-1.

- Pope-Hennessy, John (1996) [1958]. Italian Renaissance Sculpture. An Introduction to Italian Sculpture. Vol. 2 (4th ed.). London: Phaidon.

- Rowley, Neville (ed.) with Francesco Caglioti, Laura Cavazzini and Aldo Galli (2022). Donatello. Erfinder der Renaissance. Leipzig. ISBN 978-3-86502-482-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Rubins": Rubin, Patricia Lee and Rubin, Maurice, Giorgio Vasari: Art and History, 1995, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-04909-1, google books

- Seymour, Charles Jr., Sculpture in Italy, 1400–1500, 1966, Penguin (Pelican History of Art).

- Vasari, Giorgio, Artists of the Renaissance (Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects selected & ed. George Bull), Penguin 1965 (page nos from BCA edn, 1979).

- Walker, Paul Robert, The Feud That Sparked the Renaissance, 2003, New York: William Morrow. ISBN 978-0-06-174355-9, google books

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Donatello". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 406–408.

Further reading

[edit]- Avery, Charles, Donatello: An Introduction, Routledge, 1994.

- Avery, Charles, Donatello. Catalogo completo delle opere, Cantini, Firenze 1991.

- Avery, Charles and McHam, Sarah Blake, "Donatello". Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online. Oxford University Press. (subscription required)

- Bennett, Bonnie A. and Wilkins, David G., Donatello, Phaidon, 1984.

- Greenhalgh, Michael, Donatello and His Sources, Gerald Duckworth & Co., 1998.

- Leach, Patricia Ann, Images of Political Triumph: Donatello's Iconography of Heroes, Princeton University Press, 1984.

- Pope-Hennessy, John, Donatello, photography by Liberto Perugi, critical apparatus by Giovanna Ragionieri, 1985.

- Randolph, Adrian W.B., Engaging Symbols: Gender, Politics, and Public Art in Fifteenth-Century Florence, Yale University Press, 2002.

External links

[edit]- Donatello: Biography, style, and artworks on artble.com.

- Donatello: Art in Tuscany on casasantapia.com.

- Donatello at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

- Donatello: Photograph Gallery on scultura-italiana.com.

- Donatello, by David Lindsay, 27th Earl of Crawford, from Project Gutenberg.

- The Chellini Madonna on the website of the Victoria and Albert Museum

- Donatello: Sculpting the Renaissance, exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 2023, previously at Palazzo Strozzi and Museo del Bargello, Florence (2022), and at Gemäldegalerie, Berlin (2022/23). Review in TLS, 14 April 2023 Preview in The Art Newspaper, 30 November 2021.

- Sculpture in the Age of Donatello: Renaissance Masterpieces from Florence Cathedral, exhibition in 2015 at Museum of Biblical Art, New York. Review in The New Criterion, May 2015.